Table of Contents

Selection Bias

Have you ever felt cold in an office? Or noticed how many women complain about the office being chilly?

That’s because the standard room temperature was devised using a 40-year-old man weighing 154 pounds to calculate the default metabolic rate. In fact, because of biological differences (some in a study here), on average, women prefer the indoor room temperature to be 77. Men? 71. Of course people are unique, but the gender differences here are robust. Robust enough so that you’ve probably noticed it. (Feeling uncomfortably cold in an office can actually take a toll on your productivity.)

We came to the conclusion about “room temperature” because we measured subjects who had one very specific thing in common, and thought that the results generalized to everyone. This is called selection bias.

Selection bias impacts findings all the time, even when we don’t realize it. This is why most modern psychology studies aren’t nearly as iron-clad as we once thought. Results from people who grow up in an Western, Educated, Individual (as opposed to Communal), Rich, and Democratic societies can’t be generalized and said to represent everyone on earth. At best, they speak for the people in that study.

The Marshmallow Test

Surely you’ve heard of The Marshmallow Test. If not: a researcher at Stanford named Walter Mischel began testing kids’ ability to delay gratification. In his seminal study, he placed children in front of a piece of candy. Before he left them alone with it, he told them that if they could hold off eating it until one of the researchers returned—roughly 15 minutes—they’d be ultimately be rewarded with two marshmallows.

Being able to wait for the second marshmallow ended up predicting higher SAT scores and more career success. As adults, they were less likely to abuse substances or become obese; even their relationships were better. In a huge follow-up study 40 years after the original one, researchers found differences in how the brains of “delayers” and the “nondelayers” responded to rewards.

But “the original results were based on studies that included fewer than 90 children—all enrolled in a preschool on Stanford’s campus.”1Jessica McCrory Calarco. “Why Rich Kids Are So Good at the Marshmallow Test: Affluence—not willpower—seems to be what’s behind some kids’ capacity to delay gratification.” The Atlantic.

The kids who participated in the study did not represent a random sample from the population at large: they were largely white, upper middle class kids whose parents were affiliated with Stanford. They were the perfect example of what Joseph Henrich called WEIRD: Western, Educated, Individual, Rich, and Democratic.2The marshmallow test is failing the current replication crisis in psychology.

The Other Marshmallow Test

What if you, as a kid, had seen people wait for the marshmallow and come up empty-handed? What if an adult who promised you a marshmallow never followed through? You’d doubt that your patience would pay off. In fact, another study in 1970 found just this.3Richard T. Walls and Tennie S. Smith. “Development of Preference for Delayed Reinforcement in Disadvantaged Children.” Journal of Educational Psychology 61, no. 2 (1970): 118-123. Children from disadvantaged homes—if they qualified for free school lunches or their parents were on welfare—were less likely to wait (3/15 waited, compared to 11/15 kids whose parents weren’t on welfare.) There was a large correlation between the children’s ultimate choice and locus of control—or how much they thought that their own actions would influence the future. Patient kids felt that their waiting time was “instrumental in earning the more valued payoff.”

After the initial trial, the more impulsive kids received a lesson from the researchers: they were shown what they would have received, had they waited. This single, tiny intervention (seeing that candy bar in real life!) was enough to make all of those kids wait in following trials. “An interesting and perhaps more important analysis… indicates that disadvantaged children cannot categorically be termed ‘nondelayers.’”4Walter Mischel. “Father-Absence and Delay of Gratification: Cross-Cultural Comparisons.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 63, no. 1 (1961): 116-124.

“Most of the other people who have prominent theories about self-control and delaying gratification don’t acknowledge the social factors at all. Mischel, who was the pioneer of his field, emphasized trust for decades but didn’t touch it experimentally. Most of the other prominent theories don’t mention the factor at all.”

researcher Laura Michaelson

What looks like irrational behavior makes sense when you consider the whole picture and factor in someone’s life history.

- Someone might look overly paranoid—until you realize that they belong to a category of people who are more likely to get robbed.

- Your date might seem suspicious—until you learn that they’ve been ghosted, harassed, or sexually assaulted.

- Someone might look lazy—until you see how many external barriers they face and can understand their full story.

- Someone might seem impulsive—until you learn that they have no reason to believe that they’ll get a reward for waiting.

When we trust that our efforts will pay off, we make those efforts. That’s how the brain works! We’re constantly calculating the costs of our actions with the benefits of those actions, asking ourselves, “is it worth it?“

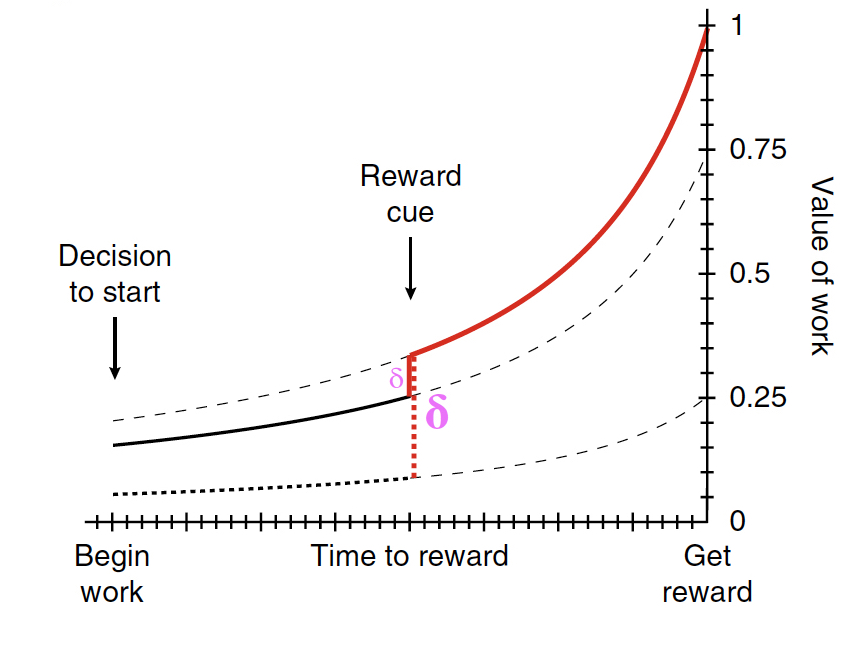

The Most Important Graph on Dopamine You’ll Ever See

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter responsible for motivation, reward, and action. These things are intrinsically tied together, because all action is motivated to go towards a reward. When we know that a reward is certain, we’ll wait. We’ll make the effort.

If you’re confused why the kids didn’t begin to always wait after that intervention, think about this: if someone tells you that saving money is good because you’ll earn interest—and then shows you a bank with guaranteed rates—would you magically start saving money, and suddenly be able to say “no” to every unplanned purchase over the next year?

It’s easy to see why an intervention wouldn’t have a big effect when we look at the big picture of someone’s life.

Let’s reframe the Marshmallow study: behavior is the product of both the person and the situation; thinking that not waiting for the marshmallow points to ingrained flaws in someone’s character, when their behavior might be a rational response to their typically shitty situation.

When an Entire Generation Doesn’t Get the Marshmallow

If you have a hard time waiting for the second marshmallow, consider your past experiences. For example, suffering from a macroeconomic shock (seeing scads of second marshmallows being yanked away) can alter your entire life, if it happens at a critical moment in your life.

In “Growing Up in a Recession,” economists found that this can happen to an entire generation5Giuliano, Paola, and Antonio Spilimbergo. “Growing up in a Recession.” Review of Economic Studies 81, no. 2 (2014): 787-817.:

We find that individuals who experienced a recession when young believe that success in life depends more on luck than effort, support more government redistribution, and tend to vote for left-wing parties. The effect of recessions on beliefs is long-lasting.

If you think that someone else is being impatient or irrational, realize that their beliefs came from somewhere. Waiting and being patient can be adaptive… if you have reason to believe that whatever you’re waiting for is going to happen.

References

- 1Jessica McCrory Calarco. “Why Rich Kids Are So Good at the Marshmallow Test: Affluence—not willpower—seems to be what’s behind some kids’ capacity to delay gratification.” The Atlantic.

- 2

- 3Richard T. Walls and Tennie S. Smith. “Development of Preference for Delayed Reinforcement in Disadvantaged Children.” Journal of Educational Psychology 61, no. 2 (1970): 118-123.

- 4Walter Mischel. “Father-Absence and Delay of Gratification: Cross-Cultural Comparisons.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 63, no. 1 (1961): 116-124.

- 5Giuliano, Paola, and Antonio Spilimbergo. “Growing up in a Recession.” Review of Economic Studies 81, no. 2 (2014): 787-817.