Exploring Tells You What to Exploit

In the Long Run, Branching Out is Surviving

Intro

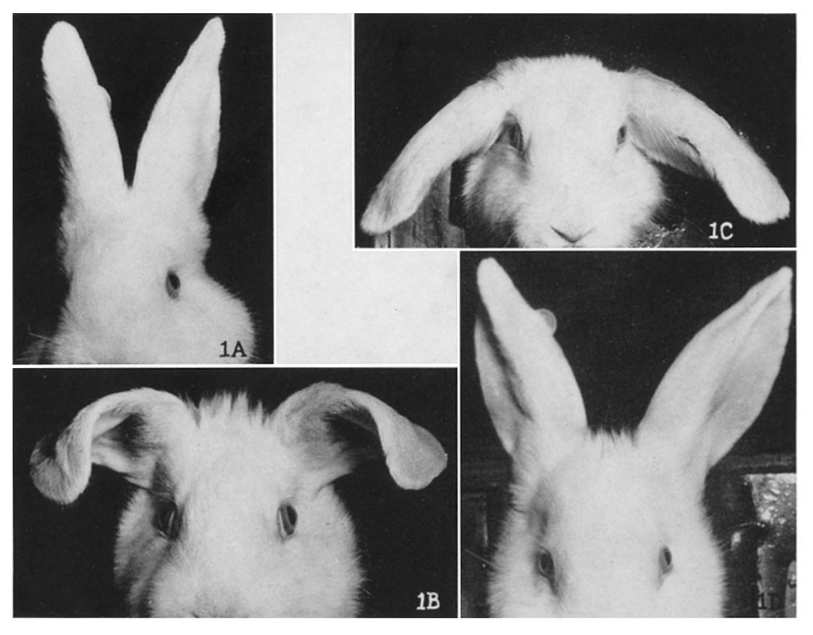

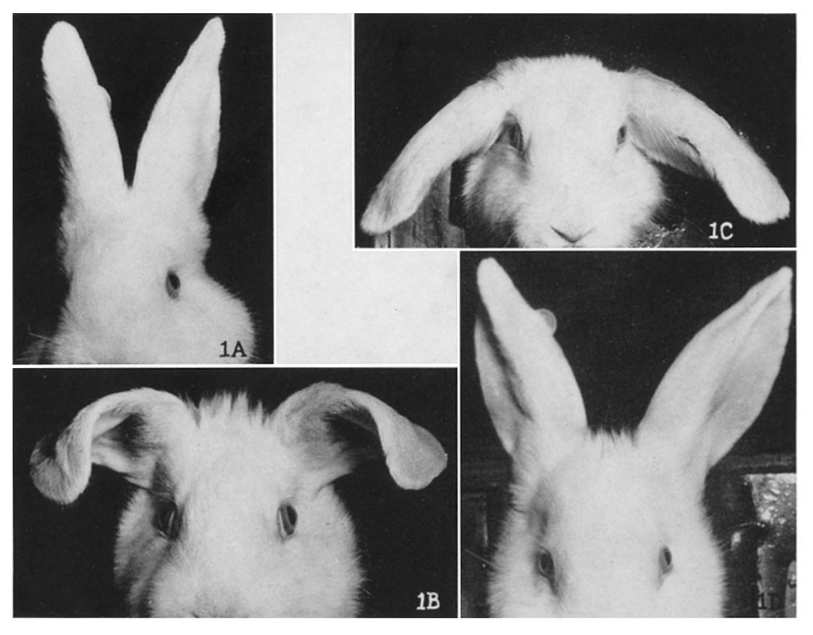

In 1954, the researcher Lewis Thomas hit an impasse while studying rheumatic fever. He was injecting rabbits with an enzyme that should have mimicked the fever’s symptoms. Instead, he got something else: four hours after the injections, the rabbits’ ears began curling at the tips; 18 hours in, they were completely wilted, flopping at the sides of their heads like tired flower petals. Thomas’s findings in the changes to the cartilage led to breakthroughs in our understanding of connective tissue what we now know about rheumatoid arthritis.

This wasn’t the first time anyone noticed the startling, consistent side effect from this particular chemical. Cornell researcher Dr. Aaron Kellner, noticed it five years earlier, but eventually chose to abandon looking into it: he was making progress on some of his other projects; his specialty was muscle tissue; the floppiness of the ears made it difficult for him to take the side effect seriously. He ended up using “floppy ears” as a sign that they rabbits had received the proper dosage: if the rabbits died, they’d received too much; if their ears didn’t flop, they needed more. Kellner was too busy exploiting his own line of research, and only looked at the bunny cartilage superficially. Thomas’s papers were featured in the New York Times, and he became the dean of NYU’s medical school.

I first read about this study, “The case of the floppy-eared rabbits: An instance of serendipity gained and serendipity lost” over 10 years ago, when I started doing research for my first book. (The working title, which I do like better, was Why Some People Have All the Luck). I focused on the stories of scientific discoveries, the founding of successful businesses, and artists/creatives taking off—good things that we can’t entirely control.

One of the most frequent ideas I came across was the Explore/Exploit dilemma. When should we explore new options, and when do we persevere with what we know?

A long-term laser focus on one topic shrinks our realm of possibilities over time, and changes the way we see the world. Kellner allegedly did all he could to test the bunny ears—in his lab. Did he have other researcher friends in other disciplines he could have brought it up to? Could he have used their equipment? When we’re overly stressed about time, anything that is not obviously relevant to our most pressing goal seems costly.

Be Curious

A recent paper published in Nature Communications explored the explore/exploit dilemma, as it related to “hot streaks” in scientific and artistic careers:

In Wang’s most recent analysis, he found that artists and scientists tend to experiment with diverse styles or topics before their hot streak begins. This period of exploration is followed by a period of creatively productive focus. “Our data shows that people ought to explore a bunch of things at work, deliberate about the best fit for their skills, and then exploit what they’ve learned,” Wang said. This precise sequence—exploration, followed by exploitation—was the single best predictor of the onset of a hot streak.

Derek Thompson

Kellner missed the floppy bunny ears and a chance to make a real breakthrough because he was “too busy” doing other things. Should I do something with a relatively known value, or go after something else—something unknown that might lead to greater outcomes and rewards? Thomas decided to pursue the bunny ears saga because he was teaching a few people in the lab and demonstrated the effect. He then decided to compare the ‘floppy’ cartilage and a bit of “control ear” under a microscope, where he discovered that the enzyme had changed the structure of the tissue.

The idea that good things come after “looking all over, and then digging like crazy once you hit oil” makes sense, but only if you give yourself the time to do so. Thomas slowed down. He was teaching. He placed a higher value on the new information. He was curious. Every encounter we have with something new informs our relationship with uncertainty. Curiosity—the act of assigning a positive value to unknown information—helps bypass this.

Exploring Tells You What to Exploit

Exploring (which I view, fundamentally, as learning) seems to have a bad reputation—a bizarre one that’s typically tied up in our short-term view of productivity. Range excellently showed many examples of how developing many skill sets or areas of competence helps people exponentially in the long run. The best scientists have the most eclectic interests.

Improvement or success is dynamic, multi-faceted, and the result of many factors coming together at the right time:

This graph is taken from an under-appreciated paper, “A Dynamic Network Model to Explain the Development of Excellent Human Performance.” In this graph, the thick black line represents someone’s overall skill level. The thinner colored lines represent the component pieces required for the skill, or system, to come together.

We’re only as good as our weakest link. What looks like someone who is underachieving or not reaching their potential may just be the case of someone waiting to find the right thing to exploit.

Here, I made my own to represent what I think happens when someone is exploring, preparing for a “hot streak.”

We judge people based on the thick black line (output — quality or quantity) without realizing what’s going on underneath it all: curiosity. Following our curiosity is the act of storing latent potential. It’s also what I like to call investing in Uncertainty Insurance. Knowing about more fields, more disciplines, and breaking down silos can only help us in the future.

In the Long Run, Branching Out = Surviving

In the long run, grit—or exploiting—can be costly. A study in 2015 demonstrated that people who score higher on Angela Duckworth’s Grit scale have higher expectations and are more hopeful. That’s great, but only if you know when to stop; subjects’ stubborn persistence and refusal to quit led to monetary costs.

When you’re obsessed with making Plan A work, “pivoting” can start to look like “a blow to the ego that I can’t afford if this doesn’t work out.” Instead of focusing on what they’ve learned, obsessives can start to focus on the downsides, viewing their time spent as a sunk cost that can’t be retrieved. Not pivoting, or failing to behave flexibly (especially during changing situations or circumstances), is also known as addiction.

The biggest mistake that people make is assuming that the future will always look like the present.

Don’t forget: in nature, exploration is key to survival. Seasons and competitors exist; new predators emerge; berries run out. The worst time to start looking for new berries is when your food source is tapped out and you’re already hungry.

Just as no one can predict when the economy is in a bubble, no one can predict when a new paradigm (or pandemic) will render their employer, skillset, or industry obsolete. Getting all of your food from the one bush is a fragile state of affairs; animals that adapt more quickly to change are less likely to go extinct. (This is why, for example, chickens survived the meteor that killed dinosaurs.) In the business world, failing to diversify leads to the greatest downfalls, and the famous business case studies: Blockbuster video; American car companies only making SUVs. Think of all of the couples who lost second homes they were renting through AirBnB.

Personality researcher Colin DeYoung equates openness to new information with intelligence. (Think of learning as the compound interest of intelligence.) It’s true in the business world, too: if the main revenue stream of all the behemoths was cutoff tomorrow, they’d be okay. Research and development is part of their DNA.

Don’t Rest on Your Laurels: Never Stop Exploring

“Explore” is just what it sounds like — trying new avenues, solutions, or ideas, and seeking new knowledge or skills. “Exploit” means digging into what you already know and maximizing the benefit from it. Getting the balance right is crucial. –David Epstein

How many times has someone been so focused on their “hot streak” that they failed to notice another potential opportunity for a discovery? We’ll never know. All it points to is the fact that ideally, exploring should never end. For knowledge work (unlike berry-finding), we don’t need to view Explore/Exploit through a binary lens. If you’re not naturally curious, or so obsessed with your productivity that you don’t see curiosity as a long-term investment (viewing it as a weird luxury that’s suitable for artists), think about it in terms of “Both/And.” Buy Uncertainty Insurance.

Get comfortable carving our new ecological niches for yourself.

Take Aways

- Explore under the auspices of exploit mode. Take a slight detour in your research to see how other divisions, companies, or eras dealt with the same problem. Write about work online and have a comments section. Push the boundaries.

- Network in other fields. If reading isn’t your thing, make friends with people in other industries.

- Mentor. Teaching will help you slow down and look at your problem through a different lens.

- Get a degree. Some people need to learn with structure; lean into it.

- Work on multiple projects at once. Make intellectual connections as you lean into your workaholism. (It’s the pandemic: no one is judging.)

- Play the infinite game. Most research or inventions that seems important today will be forgotten or replaced by a new paradigm within decades. Exploiting is playing a finite game; exploring is playing the infinite game.

- Forget Deep Work. In the long run, Deep Curiosity will save you.