Table of Contents

Huberman Podcast: Bro Science with a Ph.D.

How Bro Science Usually Starts

The Funny Thing About His Recommendations

What my doctor recommended that actually worked

The Medicalization of Everything

n.b. This starts with a personal story that helps illustrate the problems with Bro Science, but if you want to skip ahead

My insomnia

My insomnia started during the first wave of the pandemic, when I was living two blocks from a hospital in Queens. I wasn’t a total stranger to sleep maintenance insomnia1The kind when you wake up and have trouble falling back to sleep)—it was there, when I was nearing an important deadline. When I had financial troubles. When I was stressed. But this one was way worse. I used my behavioral science research skills to prescribe the best wind-down routine imaginable.

I moved my workouts to the morning, avoided sugar, stopped drinking coffee after a certain hour, and turned off my phone at night. I journaled and meditated. At night, I took baths, used an aromatherapy diffuser in my bedroom, took melatonin supplements, turned on a fan for a white noise, and played a recording of rain to help me sleep.

And oh, did I read. I read Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker. I read fiction on my Kindle. I read boring nonfiction. I printed out journal articles with titles like “Self – An Adaptive Pressure Arising from Self-Organization, Chaotic Dynamics, and Neural Darwinism – 2007,” “The Self as a Dynamical System,” and “Uncovering the Motivational Core of Traits – The Case of Conscientiouness.”

But I always woke up in the middle of the night—drugged, tired, stressed, and angry.

Fast forward a year and a half: I didn’t write for over six months, detoxing from a toxic work environment and recovering from mild burnout. My new home is next to a patch of forest in Portland, Oregon. My new health insurance allows me—get this—to see a sleep doctor.

“You’re doing all of those things? Every night?” he asked.

I was, in fact, doing all of the things. And I was still on the brink of insanity from a lack of sleep.

Huberman Podcast: Bro Science with a Ph.D.

Andrew Huberman is a researcher at Stanford whose podcast has been crushing it ever since its debút.2I was introduced to him by my brother, a Joe Rogan fan.

You couldn’t invent a better character to deliver pop health and neuroscience news: he’s white, attractive, and fit. He’s old enough to have tenure and his own lab at Stanford, but not yet at an age where his competence or ability to keep up with research would be called into question. If it existed, a drinking game based on the podcast would include phrases like limbic system, neural pathways, and dopamine—the same vocabulary you find in intro biology textbooks.

The good: the introductions to his podcasts are typically grounded in decent studies. Like most high-brow self-help—and the entire field of psychology itself—he has a tendency to draw sweeping conclusions from single studies, despite the fact that any single study does not apply to every single person. One particular study may not apply to anyone, simply because of how the math works.

For example, here’s a study that Huberman quotes liberally in his episode on habit formation:

One study from the European Journal of Social Psychology on habit formation found that subjects trying to form a specific habit (walking after a meal) took between 18 and 254 days for the habit to become automatic; in fact, some participants in the study were never able to turn that behavior into a habit. And who knows how long it stuck for? 3Lally, Phillippa, Cornelia HM Van Jaarsveld, Henry WW Potts, and Jane Wardle. “How are Habits Formed: Modelling Habit Formation in the Real World.” European Journal of Social Psychology 40, no. 6 (2010): 998-1009.

And do you know how many studies there have been on habit formation? Or how different the conditions in these studies are from the conditions in the real world? Habits are best thought of as emergent behaviors, the product of a perfect storm of influences.4Tiago Forte wrote a wonderful essay on this, years ago. a few years ago, I had no problem spending over two hours a day working out—when the gym was close, its members my main social outlet, and my trainer unfathomably hot.

Huberman goes downhill at the precise moment that you want to believe in him so much: when he makes a specific recommendation.

How Bro Science Usually Starts

My initial foray into Bro Science was at that very gym, a few years before the arrival of Ridiculously Hot and Kind Coach. I saw guys drinking what looked like shakes and turned my research skills towards building muscle and getting lean. Other people got the handbook, I thought. I ended up writing an extra chapter in my book on sports expertise and genetics to justify all of this: I had conversations about types of protein. I won nutrition challenges. I hired a nutrition coach. I weighed all of my food and ate carbs at specific times. I studied the daily schedules of top athletes.

And then, a miracle: Hot Coach arrived. Specifically, a world-class team of CrossFit athletes took over the gym (long story) and I got to see them in action every single day. Their supplements? Fish oil, glucosamine for the joints, and Amy swore by a B vitamin complex. Their diet? Counted macros; weighed their food. Ate mostly whole foods—every bit of it accounted for.

And they worked out 3 hours a day.

His Instagram account featured some protein powders—because those companies gave him money from sponsorships.

Bro Science loves the ever-popular muscle-building supplement creatine, but get a little further into the peer-reviewed research on individual differences, and you learn that a sizable chunk of people don’t respond to it because they already have enough endogenous creatine in their muscles that the powder merely creates expensive urine. It only makes a dent in your overall development—mostly, you have to spend a few hours a day at the gym. You have to sleep at least 8 hours a day (muscles are torn at the gym and repair during your sleep). And abs are made at the gym, but revealed in the kitchen: my model friends whose ads appeared in Men’s Health (I was spending a ridiculous amount of time at the gym, mind you) counted calories like crazy before a photoshoot. The photo shoot was for a supplement.

“You can take any pill when you’re counting calories, and then advertise that you got abs because of the pill. But you’re counting calories. You’re in a calorie deficit, and you have to do it consistently for a really long time to see results—which is really uncomfortable.”

-BJ Gruber

Most people don’t have role models at their disposal to explain what they’re doing wrong. Most people aren’t athletes, or authors, or 7-figure entrepreneurs or full-time influencers. Most people aren’t getting accurate feedback about their own actions.

Most people who want to lose weight often will count calories inconsistently, tell themselves that they deserve that mayonnaise (and why not?) without realizing that every little thing matters. They don’t have access to a role model right next to them to explain “it’s really boring, and it’s uncomfortable, and it sucks.”

No one wants to hear that.

Doing the big, boring stuff consistently is what makes a difference. It’s uncomfortable, which is why no one else is doing it. That discomfort was exactly what I had been trying to avoid—it’s exactly why I thought I was doing something wrong. That discomfort and insecurity about how well I was doing was why I spent so much time looking for the shortcuts online.

The Funny Thing About His Recommendations

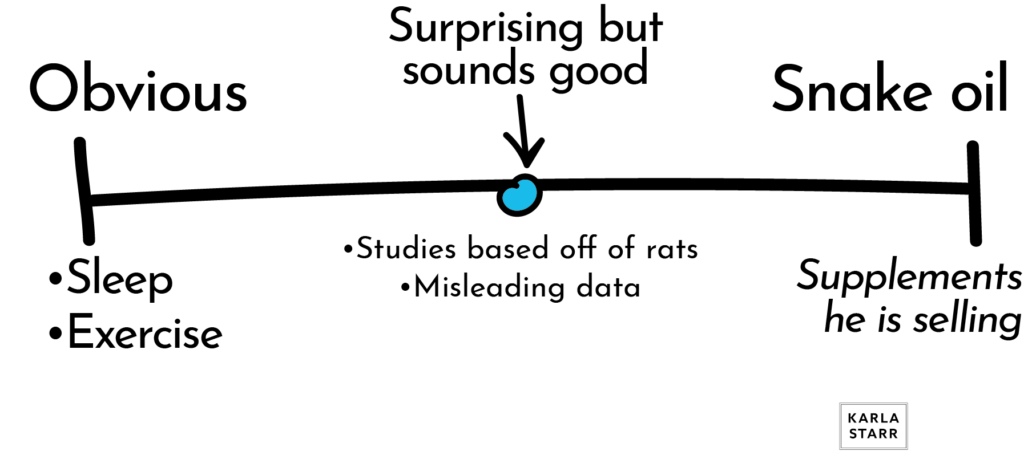

Huberman’s recommendations run along a spectrum.

Obvious

- Get enough sleep

- Eat well

- Exercise

Isn’t That Interesting?

- Look at light in the morning. (Sure, I guess)

- Light therapy

- Oxygen therapy

- Intermittent fasting

- Creatine

Do These Things Exactly Because Science (Bro Science)

Context is everything.

Because these snake oil recommendations come on the heels of NO SHIT, SHERLOCK Advice (eat well, sleep), they seem to be in good company. Nor will these things obviously harm you. What’s going on is that the effects of these “scientifically proven magic pills” are misleading, inconsistent, tiny, and often unfalsifiable.

Oxygen Therapy

Let’s take oxygen therapy as an example; the researcher at the forefront of the studies is Shai Efrati.

According to Popular Science:

In addition to his work at the Sagol Center for Hyperbaric Medicine, Efrati is the Chair of the Medical Advisory Board at Aviv, a company which owns hyperbaric clinics in Israel, Dubai, and The Villages, a retirement community in Florida. Efrati is also a shareholder at Aviv, which makes it hard to keep his research independent and raises red flags for some experts. The size of the effect was sizable, but had a large margin of error. For example, the telomere length of B cells, a type of white blood cells, increased 29.39 percent—but that could be off plus or minus 23.39 percent.

In any other field, someone’s economic motivation would be questioned—not to mention the fact that there’s a potential error of 23.39%.

Why don’t people just do studies to clear this up, you ask? Well: where would the funding be for that?

Cold Therapy

What about taking cold showers? Sitting in tubs of ice? Here’s one of the most commonly referenced studies on the matter, “Altered brown fat thermoregulation and enhanced cold-induced thermogenesis in young, healthy, winter-swimming men.” The study’s sample size is a total of 15 men in their mid-20s, looking at how much their metabolism changed during the 30 minutes they spent in a cooling session.

The resting metabolism of the experimental group increased from 2,038 calories (per 24 hours) to 3,044 calories (per 24 hours). The control group’s resting metabolism went from 2,005 to vs. 2,560 calories.

There’s a high-tech wellness center near my house claiming that cold burns more calories—”400 calories a session!”

But, no. Just look at the math.

The experimental group’s metabolism during the 30 minute session was “3,044 calories every 24 hours,” meaning that they burned a total of 63 calories during that cold session. By contrast, the control group’s “2,560 calories every 24 hours” meant that they burned 53 calories during the cold session.

These cold sessions only changed the participants’ metabolism when they were cold—not for the entire day.

In other words, 30 minutes of cold only increased the experimental group’s metabolism by a total of 10 calories. TOTAL.

What my doctor recommended that actually worked

After I explained to my wind-down routine to my doctor, he told me the the “whole ritual was probably causing performance anxiety.” His advice was sleep restriction therapy: spending less time in bed. Start off by staying up super late, later than you’d think, so that I’d completely conk out and sleep through the night. Eventually, I could start going to bed early—15 minutes at a time.

My continued insomnia was iatrogenic—caused by the very interventions meant to eliminate it. The remedy was maddeningly simple: wake up early, and stay awake. Keep myself up until it was time to go to bed. Don’t stress about it too much, because stressing and overthinking were what was making things worse. Getting up in the middle of the night is fine.

Doing nothing was ultimately what worked.

But when was the last time you heard of a podcast that was sponsored by “nothing”?

My insomnia was eventually arrested by a potent combination of decreased work stress (finishing a book), moving to a less stressful environment (from a hospital-proximate in NYC to forest-adjacent in Portland).

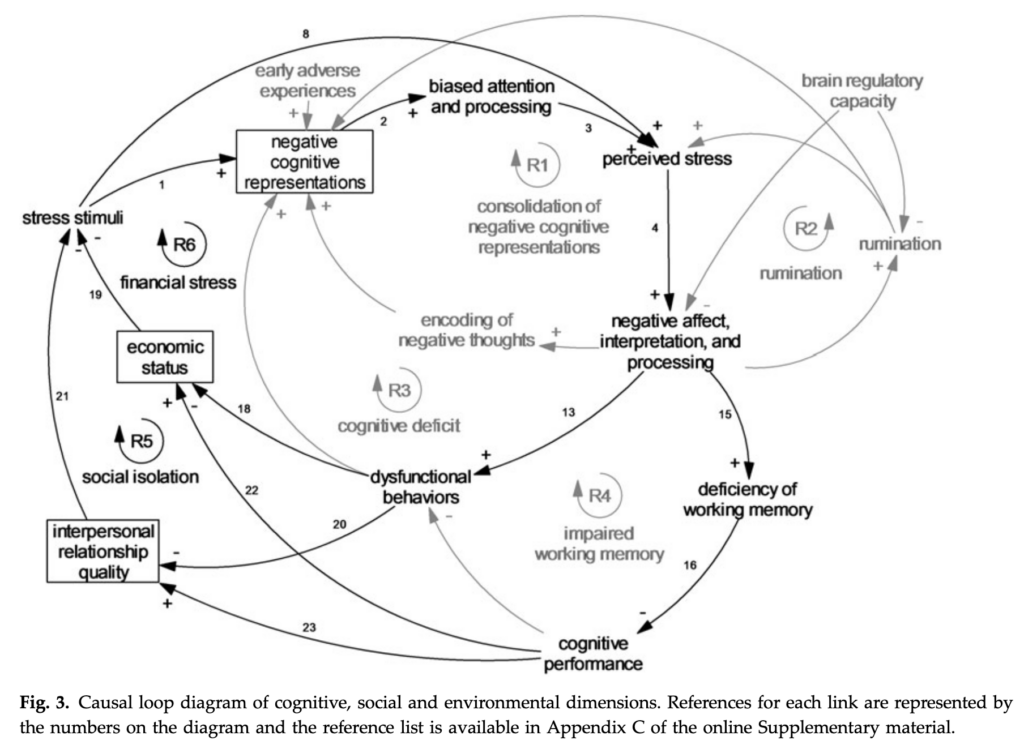

I needed to consider my entire environment, including my relationships and work, in order to lower my stress and let me sleep. I needed to stop obsessing over having every aspect of my setup “just so.” My problem was made worse by my obsession with constant optimization—by the idea that I had to have perfect sleep, that there was such a thing, and that my life needed to match up to all of the SCIENCE SAYS YOU MUST DO THIS messages.

The Medicalization of Everything

Huberman’s advice what might be called the medicalization of our problems, a process that’s as old as time, a form of social control to justify bodily interference and subordinate behavior.5Peter Conrad. “Medicalization and Social Control.” Annual Review of Sociology 18, no. 1 (1992): 209-232. PDF available here.

Medicalization is a “process whereby more and more of everyday life has come under medical dominion, influence and supervision.”

…

When a physician defines a problem as medical (i.e. gives a medical diagnosis) or treats a “social” problem with a medical form of treatment (e.g. prescribing tranquilizer drugs for an unhappy family life.)

Peter Conrad. “Medicalization and social control.” Annual review of Sociology 18, no. 1 (1992): 209-232.

Health, motivation, and how our brain actually works are all very complex systems that take place in a complex social environment.

A hyper-inward, medicalized focus does many things:

- It makes us give up our power, assume that we don’t have the answers, that we can’t trust ourselves, that there is a magic bullet

- It draws our attention away from how external factors are affecting us

- It leads to a sense of isolation

- It turns us into consumers: of supplements, of cold baths, of oxygen treatments—without being critical of the fact that there’s often a relationship between those touting these cures and those profiting off of them

Ignoring What’s Really Hard

What we really need to do is look at our entire environment, connect, and realize that there is no magic cure.

The depressed, the unmotivated—what we really need to do is look outward. What we really need to do is develop a solid sense of social support.

What we don’t need to do is stay at home, listening to someone rattle off overly-simplified studies, crossing our fingers that the supplements will kick in soon.

I recently finished ketamine treatments for treatment-resistant depression, which Huberman touted as a method of relief. Yes, they were life-changing.

They gave me enough clarity to see how I needed to change my life, and enough energy to start to make that happen. I realized that what I needed was the confidence to believe in myself and the energy to make big changes. I needed to stop medicalizing all of my problems, stop looking for pills, and rebuild it from the ground up.

- 1The kind when you wake up and have trouble falling back to sleep

- 2I was introduced to him by my brother, a Joe Rogan fan.

- 3Lally, Phillippa, Cornelia HM Van Jaarsveld, Henry WW Potts, and Jane Wardle. “How are Habits Formed: Modelling Habit Formation in the Real World.” European Journal of Social Psychology 40, no. 6 (2010): 998-1009.

- 4

- 5Peter Conrad. “Medicalization and Social Control.” Annual Review of Sociology 18, no. 1 (1992): 209-232. PDF available here.