Is Improvement Like Interest?

Improvement is Not Like Interest

Getting Better is a Dynamic Process

Dynamic principle #1: Sometimes, you have to take a few steps back

Dynamic principle #2: You’re only as good as your weakest link

Olympic-level Success Requires a Perfect Storm

For other fields, “Talent” is a tiny piece of the success puzzle

Takeaways

References

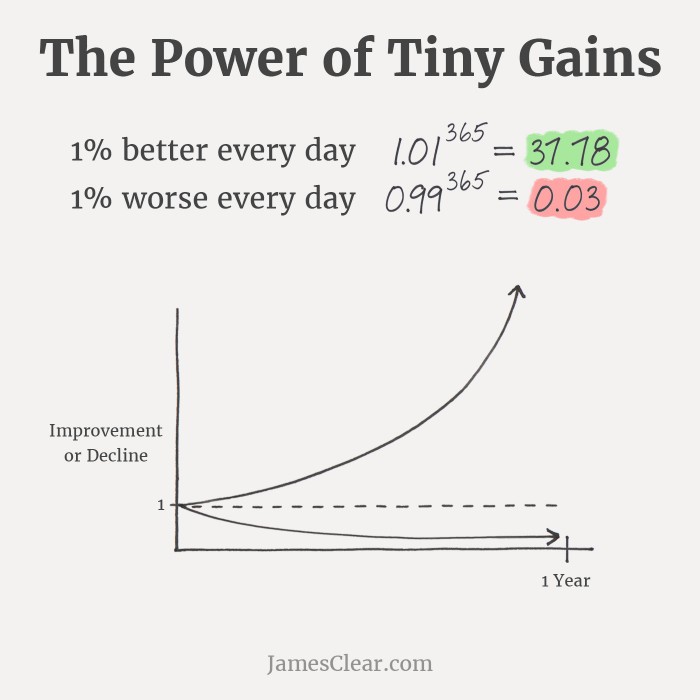

For years, I tried everything to get better at CrossFit. Or so I thought. I was so damn used to seeing James Clear’s chart on how getting 1% better every day will apparently make you a millionaire, or a CrossFit queen, after a year.

Let’s take a minute to appreciate all of its assumptions:

•Change is smooth and constant

•Change is the result of one action, compounding

•Progress is always exponential (!)

•Change is always upward

•Change is steady

•Compound interest-type progress happens outside of banks/in real life

Spoiler alert: none of these things are true.

We all want to believe that life is simple, and simple ideas are more likely to catch on because they’re easy to repeat. The more often we hear something, the more likely we are to believe that it’s true. Why would everyone say something if it was false, right? 1Just remember: science progresses one funeral at a time. And in fact, progress is often slower than expected because researchers are not immune to herd mentality and cultural conditioning. Citing popular papers is a shorthand way to show others that you’re aware of, and building on, the zeitgeist—regardless of how much you actually believe in it.

Imagine trying to make a genuine breakthrough in sociology and get away from its stalled progress, only to be told that your peers would take it more seriously if you linked it to Francis Galton’s work on Eugenics, or at least gave it a shout-out.

“Some people might feel like, ‘If only I work hard enough, I can achieve anything,’ and that may be a little bit the American dream—that if you work hard, you will be able to be someone. So if you’re not someone, if you’re not successful, that means you haven’t been working hard, you have been lazy.”

Miriam Mosing. Author interview, August 12, 2016.

Improvement is NOT Like Interest

Because of our desire to have clean, neat answers in life, it’s tempting to believe “I could be a star if I practiced more… but I, unlike those Olympians, have a life!”

But if the idea of compound interest were true, time and persistence alone could turn us all into behemoths. Alas, as anyone who has ever spent time in the real world knows, life has a way of complicating our pretty little plans.

The chart of compound interest is from the old-school era of black-and-white thinking, which uses linear logic and a traditional perspective.

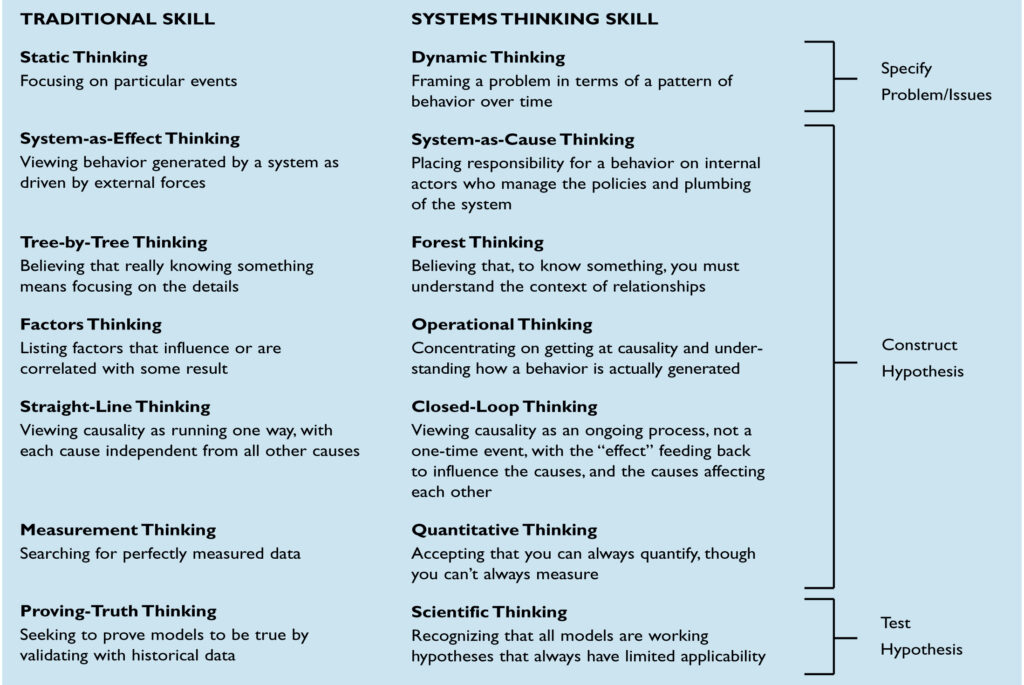

Improvement requires a perfect storm of variables coming together.

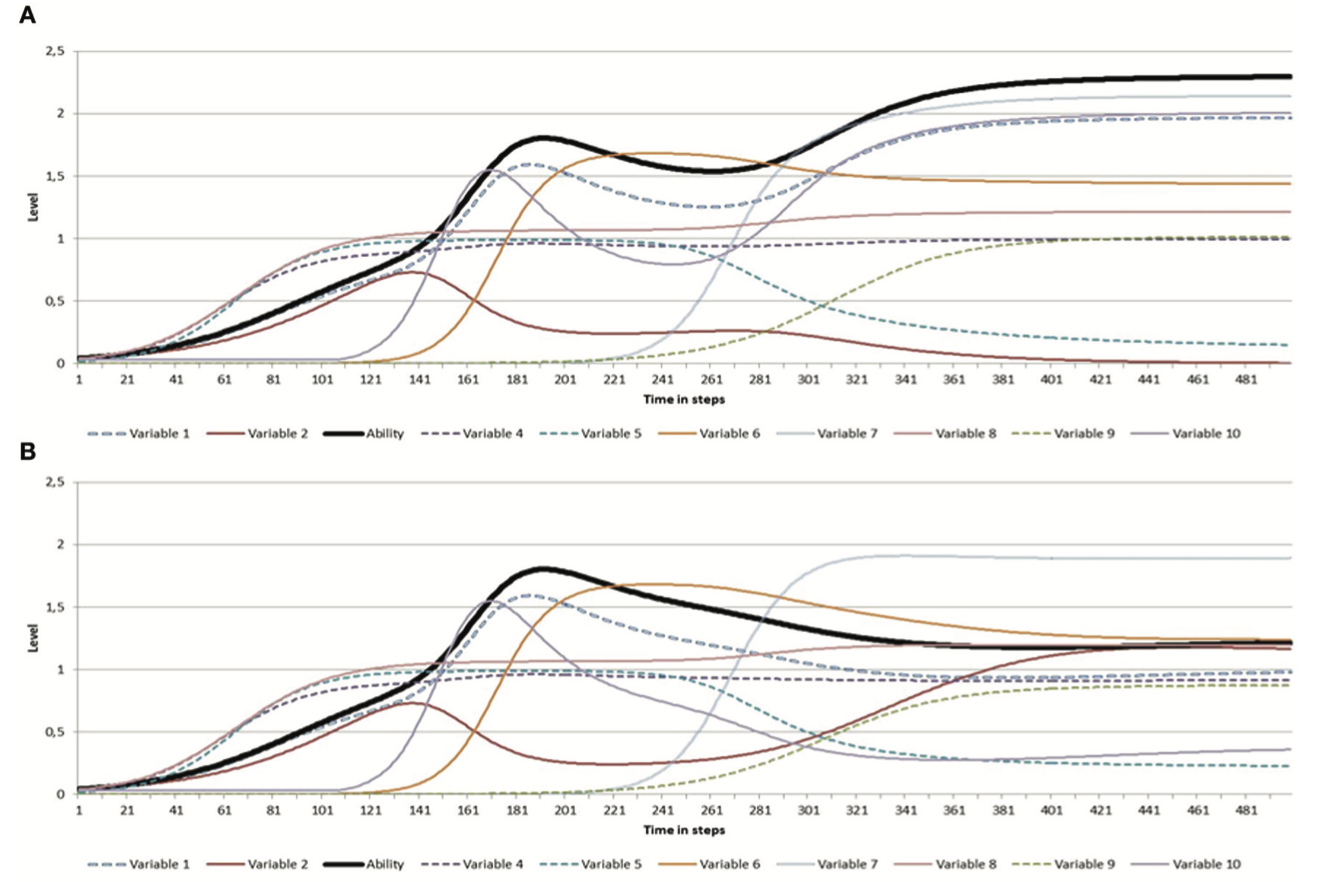

Real improvement is a dynamic process

Here are two possible paths towards a high-level performance: the top shows a steady upwards trajectory; the bottom one shows a late bloomer whose skills took off after improving a few key components.

What if you would have been an international-level late bloomer, but never found out because you gave up early?

What if someone else stuck with it, only to discover that their genes were good enough for a regional or national performance, but not the international level?

The second might tell the story of someone “someone who worked really hard, but then got a new coach/got injured/got pregnant/stopped working on their weaknesses and gave up.”

Looking at improvement through a dynamic lens helps us appreciate the complexity of all of the moving parts and how they all work together: you never know how the components are going to interact with each other.

Dynamic principle #1: sometimes, you have to go down to go up

Change isn’t always a straightforward positive trajectory. Sometimes, you have to look like a fool in the short-term to improve.

When I was knee-deep in CrossFit, I realized that my form was horrible for my Olympic lifts, the snatch and the clean & jerk. I was bending my arms, internally rotating my knees, and pulling early. I wasn’t overly concerned with improving these; I figured that they’d automatically get better with time, which is as logical as “maybe the 1,000th loaf of bread I bake will be edible, magically.”

I didn’t realize how much my weak links were holding me back because real life does not grant us the opportunity of parallel lives.

I decided to go back to square one and try to learn the movements from scratch. I had to exercise new muscles that were underdeveloped. In the short-term, it looked like I was regressing—but that’s what I had to do in order to give myself the chance to improve beyond what I was lifting.

Dynamic principle #2: You’re only as good as your weakest link

Before you obsess about being as productive as possible and doing as much as you possibly can, make sure you’re spending your time on the right thing.

Myth: improvement requires patience, so just keep going. You’ll get there.

Fact: we’re only as good as our weakest link. It’s easy and tempting to focus on the areas where we already excel, and hammer away at what we’re already doing. A few years after I started working out, I figured that I had reached my genetic potential. What I didn’t realize was that my diet was crap.

Because we can’t see our blindspots (by definition), there’s no substitute for getting external feedback on which areas need improvement.

Olympic-level Success Requires a Perfect Storm

One of the chapters in Can You Learn to Be Lucky? that I learned the most from researching was “Find Your Thing.” I wrote it, selfishly, to learn how to get better at CrossFit, but I also wanted to explore how much luck was required to achieve world-class athletic expertise, like winning a gold medal. Outliers popularized the idea that expertise requires 10,000 hours of deliberate practice. But because of the nature of sports—20,000 hours of practice wouldn’t get me to the NBA—genes obviously play a huge role. So playing the right sport is crucial.

The components required for any sport or skill are a complex mix: strength, flexibility, coordination, and executing all of the insanely difficult moves that take years of practice. Then there’s lifetime timing: winning a gold medal requires you to be in the peak physical condition of your life, typically in your early 20s. Yes, there’s actually a window, and some sports are more forgiving than others, but both your skill and physical condition have to be at their peak. So those thousands of hours of practice need to happen before you’re there.

Improvement: you have to want to practice for thousands and thousands of hours, a commitment that comes at the expense of doing anything else with that time, like having a normal life.

Margins of victory are tiny—fractions of seconds, microscopic distances, a small bit of weight—so on game day, everything has to go right: no problems with equipment, conditions, lanes, or bad referees. No crashing, false starts, or fumbling. Nothing less than your lifetime best performance will suffice, which also means that you have to have a world-class level of mental toughness, “the essential blend of personality characteristics that enables performers to excel in achievement-based contexts.”2Bell, James J., Lew Hardy, and Stuart Beattie. “Enhancing mental toughness and performance under pressure in elite young cricketers: A 2-year longitudinal intervention.” Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology 2, no. 4 (2013): 281-297.

You can work on mental skills like lowering your competitive trait anxiety or ability to focus, but your ultimate ability to modify those are subject to genetic limits—well beyond your control. Genes for how many fast/slow twitch muscle fibers you’ll develop? Practice? Equipment access? Training? How competitive is the overall field that year? Was your greatest rival performing well or having a bad day?

The one trick to winning a gold medal is that absolutely everything throughout your entire athletic career has to go right.

“Talent” is only a tiny piece of the success puzzle

To be a best-selling musician like Taylor Swift or Beyoncé, you need a great voice, unstoppable work ethic, connections, social skills/patience to make those connections, looks, mental toughness, self-control, long-term dedication, energy, and social support/resilience. You also need everything beyond your control to go right: timing, attention by the press, adoring fans.

What if you want your startup to become a unicorn? You need a great idea with impeccable execution that comes along at just the right time. You need to grow: perfect marketing, hiring, have efficient systems in place, and have money to always stay functional and operational while attracting and retaining users. You need to overcome every single obstacle that threatens growth along the way: legal issues, technical problems, bad hires, lack of users, competition, outages, and a possible portrayal of your cofounder by Jesse Eisenberg.

To be an author, you need to build up a resumé of writing to get an agent, an idea, and then have enough patience to learn about the publishing industry, write a proposal, and then find an agent. To become a bestselling author, you need to have an idea that people want to learn and buy books about, be seen as the person to write the book, release it at the right time, get media attention, have people want to share your book, and then keep the flames fanning. You need to constantly be marketing yourself.

Success in any industry with objectives that aren’t as clear cut as athletic competitions requires a favorable reception—which is largely outside of your control. But success in these more subjective industries also means that your talent for singing, songwriting, coding, or writing is simply one piece of the puzzle. You may have a book that I desperately need and want to read, but I have to hear about it enough to want to read it for that to even happen. In order for that to happen, I have to hear about it somehow. Because we’ve been living in the attention economy for so long, marketing is becoming an increasingly important piece of that pie.3 Perennial Seller by Ryan Holiday was amazing.

Flexibility: Life’s Greatest Success Hack

How do you know if you’re the equivalent of an artistic or entrepreneurial late bloomer, and just have a few kinks to iron out before things take off? You don’t. You never do. And when some of these factors are outside of your control, you never know if you’re ever going to reach your goals or become as successful as you want to be. The people who ultimately get to greater levels are the ones who invest resources towards getting to the top, and simply keep going until they get lucky or their big break.

A while ago, Cal Newport wrote that shipping trumps serendipity: just keep doing things at the nexus of your areas of expertise. The problem was that success as a Rhodes Scholar relies on a lengthy CV showing a history of focused success. In the non-Rhodes Scholar aspects of life, i.e., all of it, success can find you on your very first try. It just depends on all the other factors: are you cute? Right place? Fulfilling a niche? Cultural markets don’t care if your expertise in an area runs deep; they just want to know if your work is packaged well enough to get noticed, good enough, and hits a nerve at the right time.

Takeaways

- Constant, compound interest-like improvement is impossible. Because of the complex interplay of variables seen in dynamic systems, you can unexpectedly plateau, get worse, or see sudden growth spurts.

- Work on your weaknesses. Don’t be afraid to look like a fool in the short-term.

- You’ll only reach your potential if you fall in love with the process of getting better.

- For creative fields, if you’re focused on sales, B work in A+ packaging is better than A+ work in B packaging.

- People are always searching for the magic bullet, the mythical productivity tool: this doesn’t matter at all if you’re not spending your time where it is needed the most. You probably won’t figure that out reading a book, so get a mentor or coach.

- There is no magic bullet: just a million little bullets coming together.

REFERENCES

- 1Just remember: science progresses one funeral at a time. And in fact, progress is often slower than expected because researchers are not immune to herd mentality and cultural conditioning. Citing popular papers is a shorthand way to show others that you’re aware of, and building on, the zeitgeist—regardless of how much you actually believe in it.

Imagine trying to make a genuine breakthrough in sociology and get away from its stalled progress, only to be told that your peers would take it more seriously if you linked it to Francis Galton’s work on Eugenics, or at least gave it a shout-out. - 2Bell, James J., Lew Hardy, and Stuart Beattie. “Enhancing mental toughness and performance under pressure in elite young cricketers: A 2-year longitudinal intervention.” Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology 2, no. 4 (2013): 281-297.

- 3Perennial Seller by Ryan Holiday was amazing.