TABLE OF CONTENTS

Patience isn’t just a personality trait: it’s a response to environmental regularities

THE MARSHMALLOW TEST

Surely you’ve heard of The Marshmallow Test. If not: a researcher at Stanford named Walter Mischel began testing kids’ ability to delay gratification. In his seminal study, he placed children in front of a piece of candy. Before he left them alone with it, he told them that if they could hold off eating it until one of the researchers returned—roughly 15 minutes—they’d ultimately be rewarded with two marshmallows.

The children who were able to wait for the second marshmallow not only scored higher on their SATs, but reached higher levels of career success than their grabby peers. They were less likely to abuse substances or be obese; even their relationships were better. In a huge follow-up study 40 years after the original one, researchers found differences in how the brains of “delayers” and the “nondelayers” responded to rewards.

Isn’t it obvious that the ability to delay gratification is important? James Clear made that the theme in “40 Years of Stanford Research Found That People With This One Quality Are More Likely to Succeed.”

THE OTHER MARSHMALLOW TEST

We hear much less about Mischel’s earlier tests in the southern Caribbean islands of Trinidad and Grenada, when he asked hundreds of 8 to 14-year-olds if they wanted a small candy bar now or a huge one in a week.1Walter Mischel. “Father-Absence and Delay of Gratification: Cross-Cultural Comparisons.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 63, no. 1 (1961): 116-124. Kids in homes without fathers wanted what they could get, right now; another examining the choices of young kids in West Virginia, found the same results: that children from disadvantaged homes—whose parents were on welfare, or kids who qualified for free school lunches—were less likely to wait for larger rewards.

To see if anything could make them wait, researchers tried a few adjustments. In one, they turned the test into into a teachable moment. The researchers simply showed the kids the candy that they would have received—they made that reward real.

This single intervention—simply showing them what they would have received, if only they had waited—completely reversed the lopsided effects in later trials.

“An interesting and perhaps more important analysis,” wrote researchers, “indicates that disadvantaged children cannot categorically be termed ‘nondelayers.’”

If it was a deeply personal flaw, how did they all immediately learn patience? And then why were researchers later dismayed to learn that brief “self-control interventions” didn’t last long?

PATIENCE ISN’T JUST A PERSONALITY TRAIT

The now-standard interpretation of why some kids couldn’t wait is to blame personal shortcomings: like impulsivity, self-control, or severe time discounting. But the study shows that the kids’ ability to wait depended on whether or not they thought their patience would actually pay off. The rules that people follow depend on what was consistently reinforced during their developmental stages; suddenly saying “you can trust me this time!” won’t magically make someone forget all the years that adults have made false promises.

Patience isn’t just a personality trait: it’s a response to environmental regularities. Constantly updating our mental model of how the world works would be far less efficient and lead to many more costly errors.

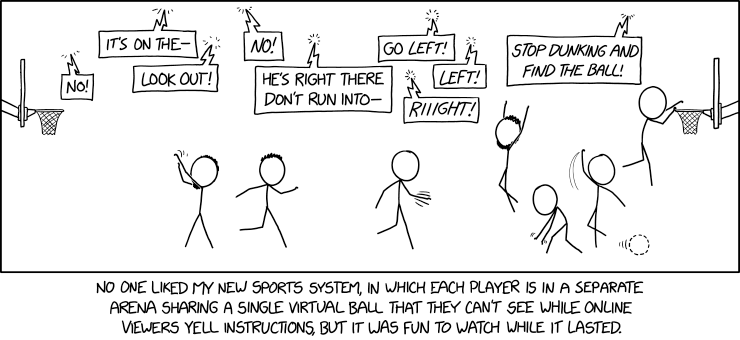

Grit, the ability to delay gratification, and perseverance don’t always lead to good things, because the situation is always changing. Life isn’t like a game of basketball. It’s more like a bizarro game of basketball where the rules are always changing without warning.

To get this whole picture of what influences our behavior, we need to zoom out and look at the big picture. A system is simply something defined by its boundaries and energy that has many interacting parts. You are a system, and are influenced by your body, self-concept, social circle, culture, family, and the larger communities you’re a part of. Behavior is the only part of you that we see, but it’s the very last step, the tip of the iceberg—lots of things affect why we do what we do.

We don’t enter psychology studies with the same mental models of how the world works. If you’re in an unstable environment, or the future isn’t clear, it’s actually smarter to take the candy bar that’s right in front of you. (Long-term survival depends on behavioral flexibility, not persistence.)

If you want to stop bad patterns or habits, survive and thrive in uncertainty, and be able to make progress on your goals when everything around you is changing, the first step is to zoom out.

Look at the big picture. Learning to wait for the candy isn’t the most important skill to learn. Knowing when to wait is.2You may have heard about the Dunning Kruger effect. If you don’t know a lot about a topic, it’s easy to overestimate how much you know. The more that you do know, the more you realize: things are complicated. Psychology is finally coming to terms with the fact that our behavior is also governed by a million forces. If you ever hear “What’s the consensus on how people respond to X?” you have every right to cringe.

- 1Walter Mischel. “Father-Absence and Delay of Gratification: Cross-Cultural Comparisons.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 63, no. 1 (1961): 116-124.

- 2You may have heard about the Dunning Kruger effect. If you don’t know a lot about a topic, it’s easy to overestimate how much you know. The more that you do know, the more you realize: things are complicated. Psychology is finally coming to terms with the fact that our behavior is also governed by a million forces. If you ever hear “What’s the consensus on how people respond to X?” you have every right to cringe.