This interview with Devon Price is the best that I’ve read in a while. Price, the author of Laziness Does Not Exist, started rethinking their entire view of productivity after reflecting on their pet chinchilla, Dumptruck.

“He’s never been productive in his life… So I think animals help us remember that we shouldn’t have to earn our right to exist. We’re fine and beautiful and completely lovable when we’re just sitting on the couch just breathing. And if we can feel that way about animals that we love… then we can start thinking of ourselves that way, too.“

One of the many reasons I adopted Daisy was to force me to become more present in my own life: fewer screens, more sun. Less screen time and more presence has helped me learn how to become exquisitely happy when I’m not doing anything. But lots of long walks did help me develop the Relativity Theory of Motivation.

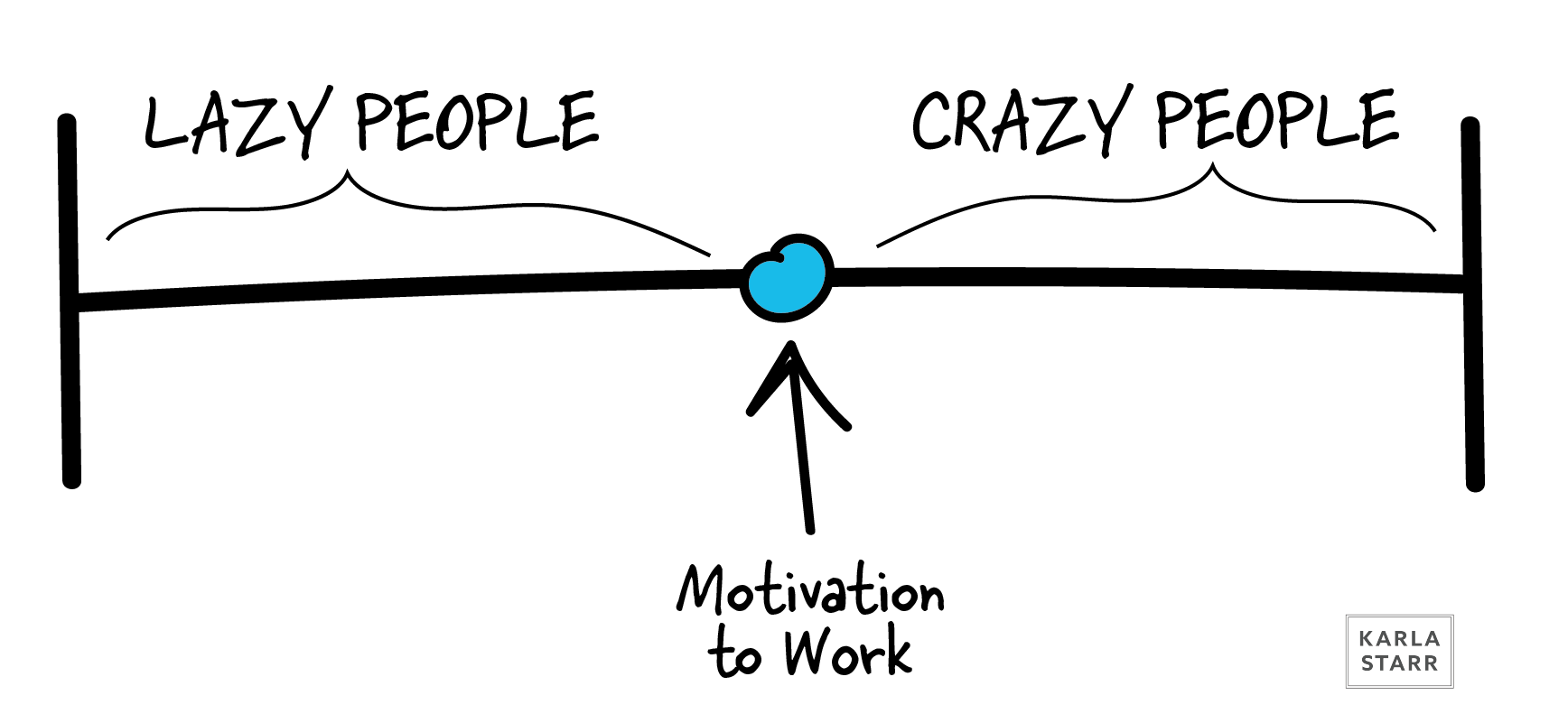

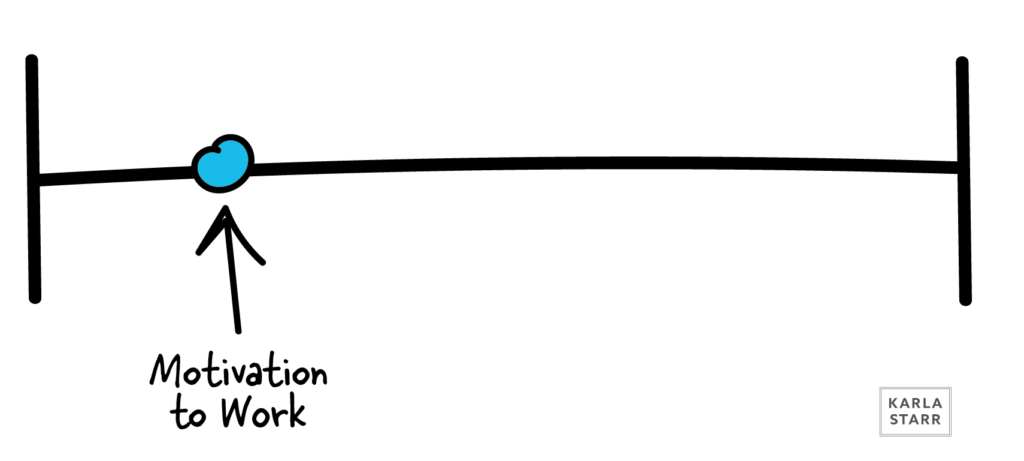

Last year, I was living in New York and taking 60 mg of Adderall a day:

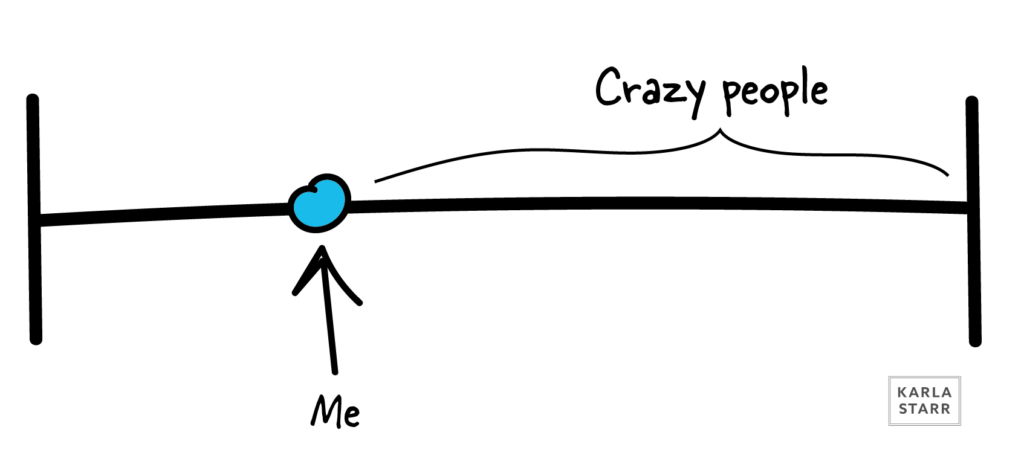

I, of course, didn’t see myself as an outlier—I just saw all the reasons for why I was doing what I was doing: I have a book contract; this is what people do; I’ve got a great opportunity; I’ve wanted to write books since I was 8; I’d rather do this than have an office job and this is the price I’ve got to pay; I really do love this above all else…

Here’s what I saw:

That right! I was fine: everyone else was lazy.

That COVID Shift

But in the last year, let’s just say that there’s been a shift. I burned out. COVID happened. I moved from New York to Portland. I’ve been paying more attention to my health and relationships. I’ve been detaching from dysfunctional relationships, ones that were zapping my energy, self-worth, and driving me to work longer hours.

Now, instead of merely limiting the amount of time I spend in front of a screen, I take care of the other side of the equation. I’m also making sure that I do a bunch of other things everyday, to give myself a well-rounded life and prevent burnout: exercise; social time; reading time; wandering with Daisy; cleaning; creating; learning new skills.

The silver lining of having this mental space is that I’ve been able to reconsider the link between my personal self-worth and my productivity: I no longer feel guilty working fewer hours. I enjoy taking long walks in the forest. I don’t feel compelled to constantly buy things, go out, spend money. Downsizing is worth it.

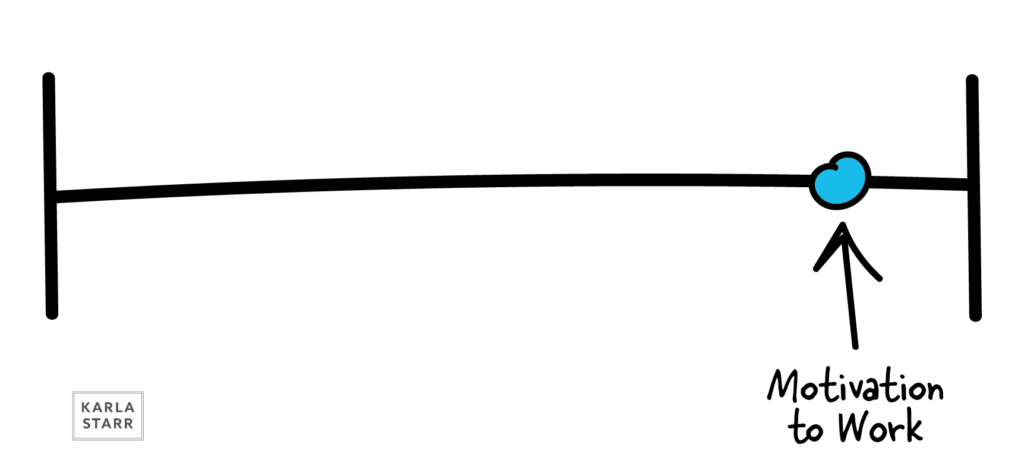

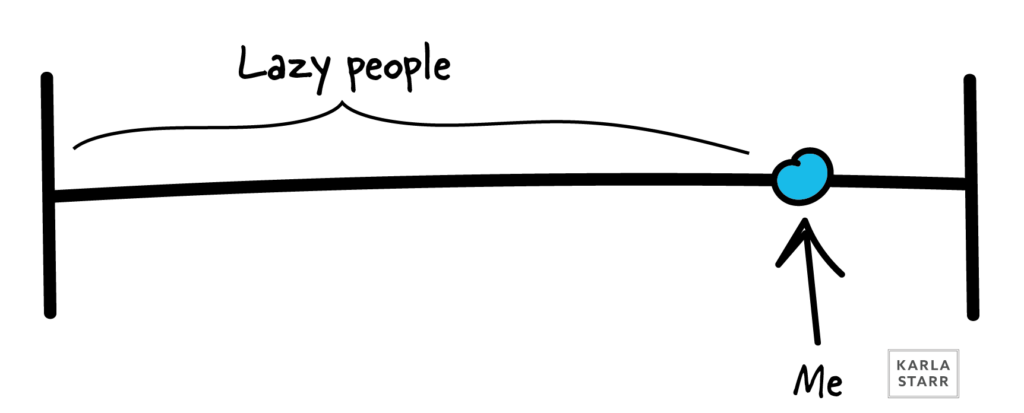

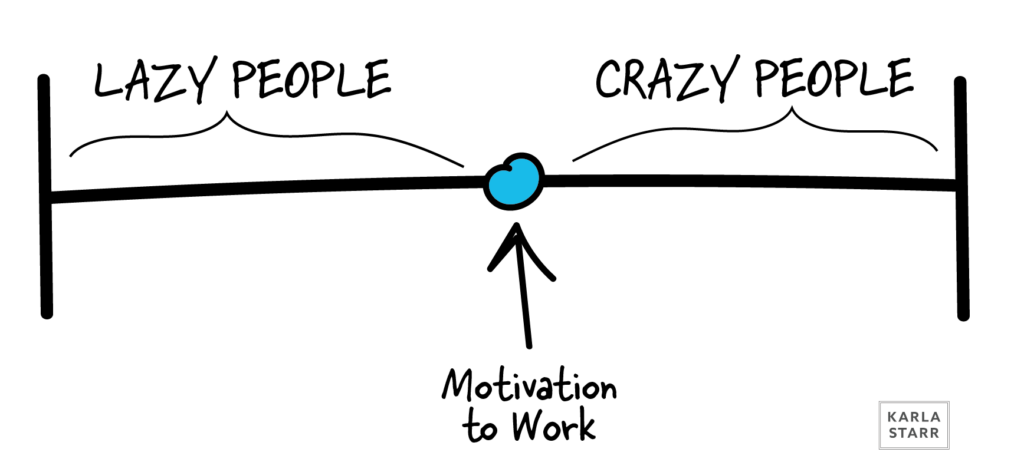

Now, I feel like:

But at no point do I see myself as lazy—sometimes, I just see myself as in need of a rest. And I see other people with unbalanced lives.

Throughout all of this, I’ve had no idea what my objective level of motivation is. I can’t. No one can glimpse into other people’s lives and get an accurate assessment of what they’re doing, how much they’re doing, how well, and with how much energy and vigor. Everyone is in their own little bubble without even realizing that they’re in a bubble. Because academics know lots of people—students and faculty—they think they have a good sense of what’s what in among a broad stretch of humanity. It’s possible to know a lot of people

What I have noticed, during my transition from workaholic to work-live balance nut, is that my judgment has become a moving target. It doesn’t matter where I am:

Still, this feels immature—unwise—since calling people “lazy” or “crazy” continues to judge my level of energy/output as the correct one. And it’s not objectively right, since “objectively correct” level of output does not exist.

Do I really know how other people spend their time? And why should I care? All I know is that I’m doing what I need to do for myself today; everything else is subject to change.

Sometimes, I get caught up in a project and find myself in a state of flow for hours. Sometimes, I just want to watch What We Do in the Shadows and play around with Adobe Illustrator or bake bread or go on Pinterest to recharge my batteries.

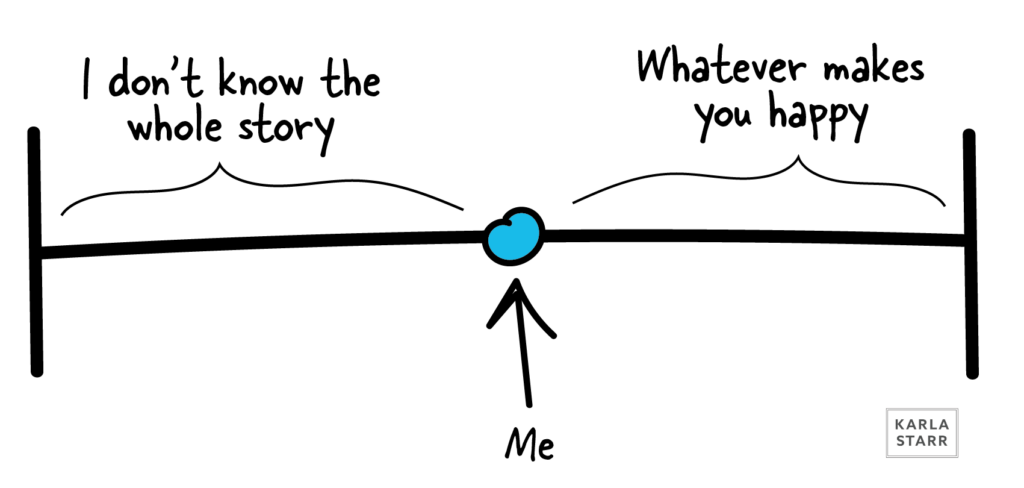

To account for life’s constant change, I present the Relativity Theory of Motivation (Wise Version):