In this post…

Different things become challenging

In the long run, personal resourcefulness is key

A few ways I get out of the “everyone has it easier than I do” self-doubt downward spiral

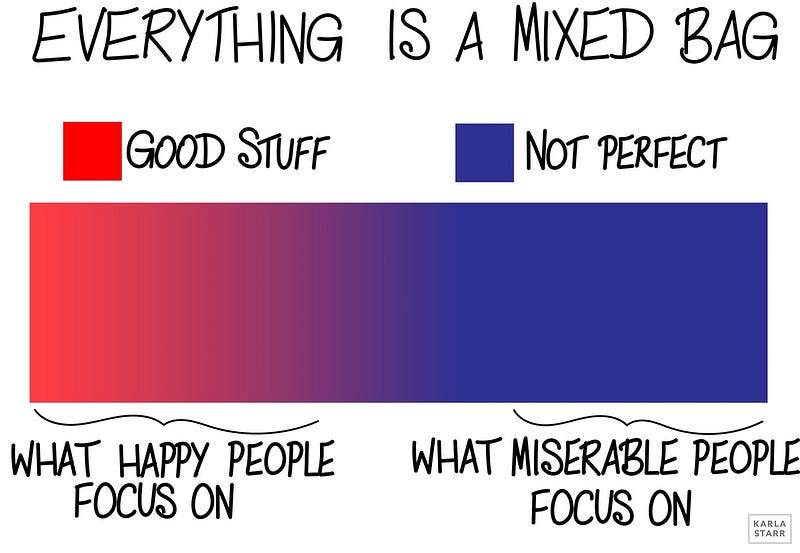

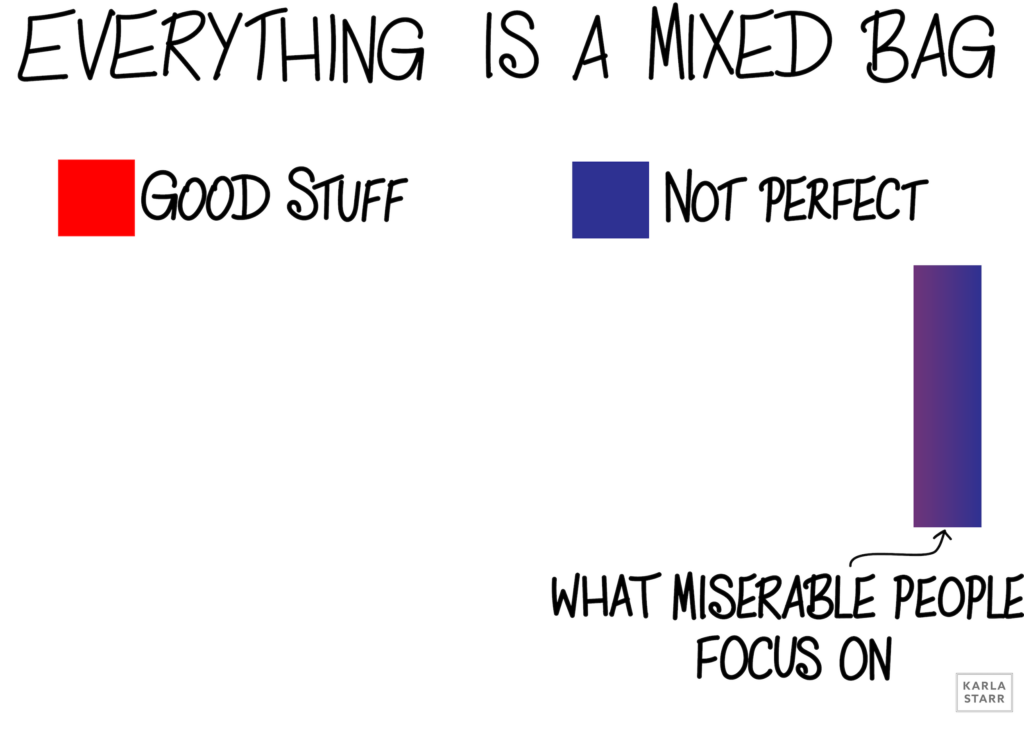

Direct your attention where it is most useful

Most self-care revolves around activities that fill your tank

I used to think that there was a magic level where people started getting things handed to them and life became easy. It’s a belief that started when I was young, whenever my grandmother or mother would reference someone who lived near Deerhurst, or attend Nichols, or a family whose patriarch was a lawyer or doctor.

It’s an excuse I’ve used countless times: this thing that’s hard for me is easy for that person, because they can hire people to do it/have an assistant/get that thing for free. They get X for free.

That’s whining. That’s assuming. That’s ruminating. And wallowing and ruminating over how you assume that other people have it easier is guaranteed to make you miserable. Trust me.

Three years ago, I got an insane promotion and started working with one of my idols, and learned a hard truth: The easy level does not exist. Instead, different things become challenging.

- “Getting money must be easy for that author—he has a book out, so he can apply for those grants.” Fact: they still have to apply for those super-competitive grants, still have to pitch those super-competitive articles.

- “The publishing company must have paid for those headshots, photos, and that website.” Fact: publishing companies pay for books to be published, but the other expenses are largely up to authors. Bloggers, entrepreneurs, and 99% of authors pay for their own photos, websites, social media management, and anything else they put out into the world.

- “They probably have someone to do their social media.” Maybe! But they still have to pay them. Hiring and managing people is a time-intensive task. When you make enough money to outsource something, you still have to find someone to entrust with content and passwords (!). You’re still entirely responsible for the content.

- “They know people—they have connections.” There is no magic grab bag of contacts you get for reaching a certain level; connections only get you so far. (A-list actors get offers to throw their hats into the ring and audition for parts. As an casting director once reminded me, everyone wants to work with Martin Scorsese. So everyone—save, perhaps, for Leonardo DiCaprio—needs to submit an audition.) Connections may open the door, but won’t get you hired. Everyone faces rejection. Even Paul Bloom—a Yale professor, author, public intellectual—has lamented on Twitter that at least half of his submissions to the New York Times opinion section don’t get published. Half. Resilience is important for everyone.

- “It’s easy for him to improve as an athlete: he’s a professional and can train for 4 hours a day.” I used to think this before I saw, firsthand, how much work goes into getting and maintaining sponsorships. And when you spend 4 hours a day training, you’re not just competing against randos from the gym. You’re up against other people who also spend 4 hours training… and maybe even more time on nutrition, recovering, sleeping, honing on skill work, or improving their mental toughness.

- “They’re a staff writer. They have a stable income.” Once you get hired by a magazine as a full-time writer, you still have to find and pitch ideas to your editor. You don’t have tenure; getting fired is always a possibility. Rock star writers need to justify their income.

- “They don’t have to look for clients—clients find them.” Once your talents get recognized, you get more responsibilities and need to manage your time better. Expectations about what you can deliver skyrocket, and so does stress.

- “They don’t have to go to an office to deliver that presentation—they can work from home.” Okay, so now you’re responsible for the setting, lighting, audio, camera, and all of the technical details.

- “They make lots of money, and can outsource that thing.” Once people think you make lots of money, they start charging you lots of money.

- “They can hire people to do consulting/branding/PR.” I’ve shelled out so much money for advice that was not worth any of the money. If I could offer any branding/consulting/PR advice for solopreneurs or authors, here it is: just pretend that you’re a white guy with a Ph.D., and all of your ideas are golden. Just pretend you’re golden. And if you really want to hire someone, hire me and I’ll charge you 1/10th and help you figure it out on own.

In the long run, personal resourcefulness is key

Those ahead of you in any competitive field may have overcome whatever difficulty you currently face, but I think it’s a mistake to assume that others are playing on an “easy” level. Typically, this happens when we’re narrowly focused on whatever we currently find challenging. Stewing in a sense of powerlessness decreases motivation: when we think that life isn’t fair, we assume that our actions have less value.

Once you overcome your current difficulties, the stakes will become higher; the next level will contain new challenges that you can’t see from where you are—things that no one posts about, because, if we’re all honest, when was the last time you posted about your professional difficulties in a pubic setting?

Working with Chip, I was fortunate enough to jump ahead a few levels and learned that there’s always something. And because there’s always going to be some unknown and unpredictable challenge up ahead, the best kind of insurance you can have for your future is confidence in your ability to figure things out. Because eventually, you’ll run into a situation that neither Google, a friend, nor your bank balance can solve, an internal sense of resilience and belief in your ability to solve new problems is the most bulletproof advantage you can bring to life.

We “move up” to different levels because of a trait called core self-evaluation, which measures our self-esteem, believe in our ability to figure things out, and emotional stability. 1like the construct core self-evaluation for this idea, the “fundamental premises that individuals hold about themselves and their functioning in the world” that’s linked to objective career success.

No one succeeds alone. We all need people.

But to what extent do you feel like you need people?

My friend Molly can’t send an email without showing it to multiple people, but if you ’re always emailing, calling, and depending on others, you won’t have any practice solving your own problems once something truly novel comes along.

Productive and unproductive habits compound over time, and can create wildly different trajectories over the long haul. Just imagine how much further you’ll be able to get by being able to quickly handle small bumps in the road, without freaking out. Without telling yourself “it’s a sign that it wasn’t meant to be!”

Overcoming the “everyone has it easier than I do” spiral

Here’s a good place to look at the difference between self-pity and self-compassion.

When we’re stuck in self-pity, we turn inward. We separate.

When we can be kind to ourselves, we can head towards self-compassion. We can use this as a moment for empathy and realize that others are also in our situation.

When individuals feel self-pity, they tend to become immersed in their own problems and forget that others have similar problems. They ignore their interconnections with others and feel that they are the only ones in the world who are suffering. Self-pity emphasizes egocentric feelings of separation from others and overdramatizes the extent of personal suffering. Self-compassion, however, allows one to see the related experiences of self and other without this type of distortion or disconnection.

Self-compassion also requires taking a balanced approach to one’s negative emotions so that feelings are neither suppressed nor exaggerated. This equilibrated stance stems from the process of relating personal experiences to those of others who are also suffering, thus putting one’s own situation into a larger perspective…

The idea behind self-compassion is that, paradoxically, healthy and constructive self-attitudes stem in part from de-emphasizing the separate self instead of from building up and solidifying one’s unique identity.

From “Self-Compassion: Moving Beyond the Pitfalls of a Separate Self-Concept,” by Kristin D. Neff, in Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego.

Direct your attention where it it most useful

Attention really is that “one neat trick!” in life — controlling or directing your attention well is what helps prevent a lot of other problems. It’s important to not beat yourself up if you find yourself focusing on that crap, though: our attention automatically zooms in to the things that we need to fix in order to survive. Honing in on our difficulties is a feature of the brain, not a bug.

The difference is that our brains evolved in an environment where more of our problems were directly related to survival. Today when we feel criticized, threatened, or ignored, it’s not an imminent precursor to isolation and possibly death — but our stress response still acts like it.

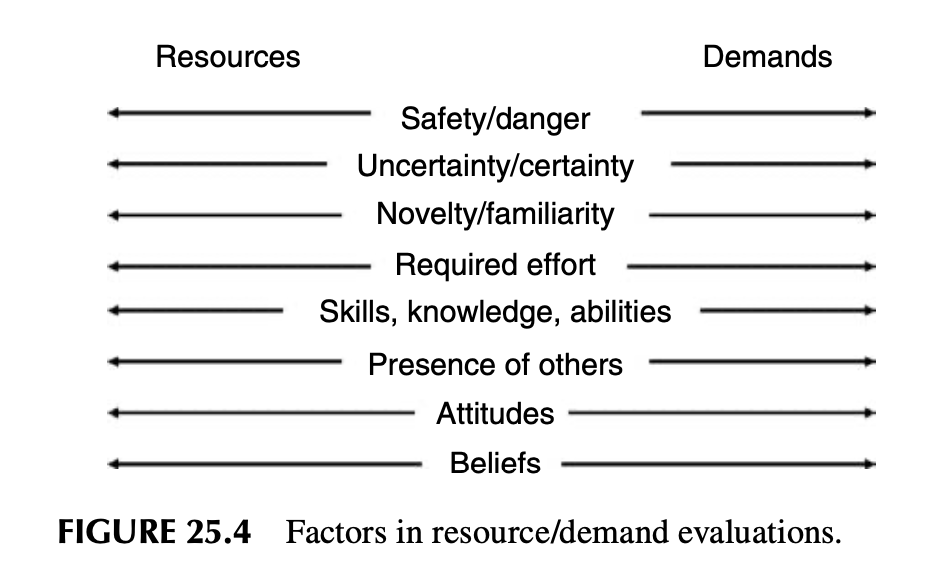

Resilience at any levels requires us to focus on using our personal resources to get over the stuff that we want to improve or overcome. Focusing on reasons why we think others have it easier is a recipe for misery and stress because it shifts our perception of how many resources we have: when we compare our bank account to Elon Musk’s — and act like that’s the only thing in the world we need — things feel bleak.

When I’m feeling sorry for myself or angry at the world, I shift my attention to things that fill my tank.

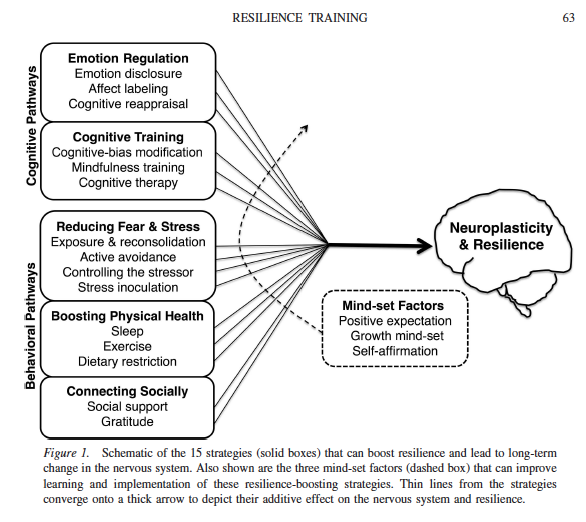

What sound like self-care clichés (gratitude, exercise, social connection, laughter) are ways to promote resilience:

- Gratitude

- Exercise

- Social connection

- Laugh! (Bonus points if you can laugh at yourself)

Resilience-promoting exercises are effective methods of reducing stress because they make us feel like we have more resources and fewer demands.

And this is why it’s so harmful to ruminate on reasons why we think other people have it easier: the second we start to compare to someone who we assume has more resources, our own ability to persist suddenly seems inadequate. We end stress ourselves out, needlessly. We prolong our own suffering.

We never really know what other people’s lives are like behind closed doors. Whether that person who just got a house/had a child/promotion has it better than you. Focusing on how you think other people’s lives are easy is a short-cut to separation, contempt, and wallowing in misery. Wallowing in self-pity is time that I’m not spending doing something restorative for myself, beneficial for my dreams, or helpful for other people. Conjuring ideas about other people’s lives — and then getting angry at those ideas — guarantees that I’m wasting time and making things harder on myself in the meantime.

When I start getting angry that things seem easier for others, or that others have it better—no one else even knows my pain—it’s easy to turn inward, hyperfocus on what seems awful, and interpret everything in a way that backs up my “things are awful and my future is bleak because other people have it easier” belief.

What really helps me is to get out of my head entirely and try to make someone else’s day better. Being able to reach out and connect gives me strength in simply knowing that I’m not alone. Most current schools of self-help or self-improvement miss this important step: sometimes, the best thing we can do to help ourselves is to help someone else.

- 1like the construct core self-evaluation for this idea, the “fundamental premises that individuals hold about themselves and their functioning in the world” that’s linked to objective career success.