“Laziness is built deep into our brains.”

– Daniel Kahneman

Where Our Hunches Actually Come From

Let’s say that we’re trying to select a movie for the night with our friend/family/partner. Here’s our brain in a pristine state, before we’ve gathered any evidence:

You’re scrolling on your TV and see a movie you’ve somehow never heard of—but it has an actress/genre you really like—and it’s way better than what we were going to suggest—so the scale starts to lean to the side of THAT’S A GOOD THING:

Next, we learn something annoying: maybe it’s kinda long, or has a hefty rental fee even though we’re already paying for all of these streaming services, which might be a small marble on the side of NO:

Why is it a small marble? Because it’s Covid and you’re not going anywhere, so who the hell cares how long it is? And isn’t $5 a small price to prevent you from spending an hour trying on pick out a movie that everyone can agree upon? We give more weight to criteria that we deem important, which fluctuates wildly depending on our mood or anything else in the environment that we’re not entirely away of.

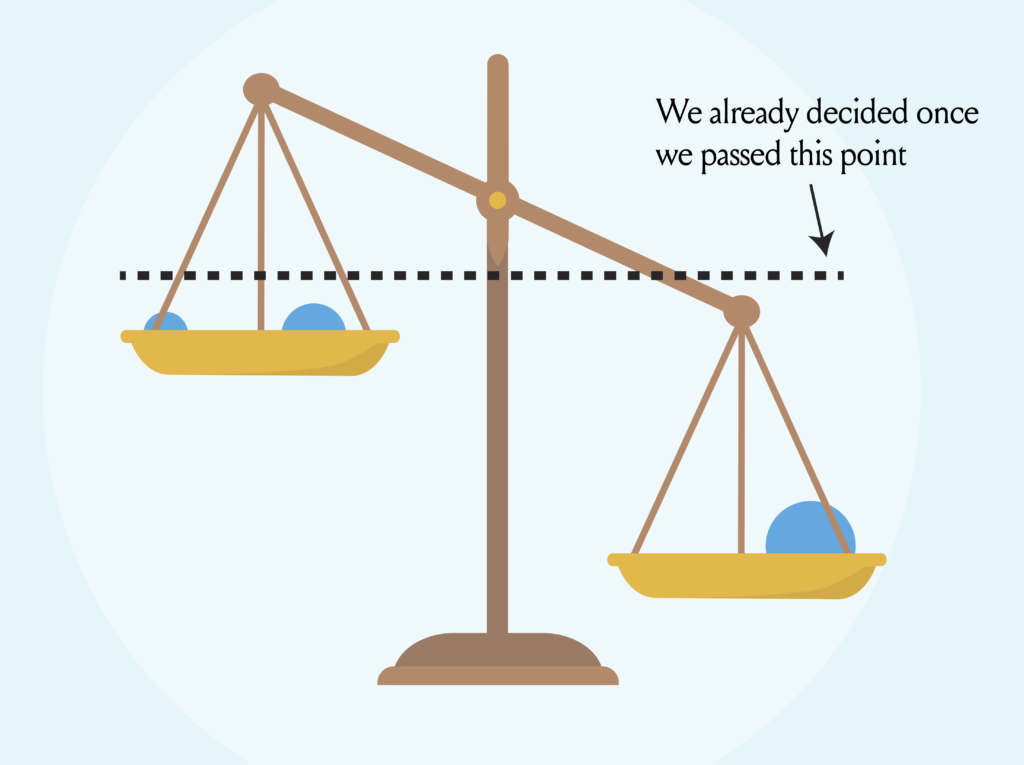

Here’s what happens when our mind is already made up, and we find out something other slightly annoying piece of information—say, our partner/friend doesn’t want to watch it.

It doesn’t matter.

Once we’ve gathered enough information to form a hunch (even if we don’t realize it), we start gathering information to back that up—even if we don’t realize it.

“People think that the brain is like a computer,” says personality and neuroscience researcher Colin DeYoung. “If you think about it, a better model to use is a robot with a limited energy source.”

Thanks to 5 billion years of evolution, your brain is king of one thing: achieving its goals while using as little energy as possible. Laziness is built deep into our nature. Whenever we think, we take shortcuts. “The brain has no gimmick, just five billion years of research and development.” Over the course of millennia, our brain has developed countless ways to successfully adapt to its changing environment and make decisions based on little information.

If we go back in time, we can see that things we learn, believe, and do (beliefs, preferences, skills, communication) are all pretty malleable. And not just over the course of evolution: there’s a good chance you’re mildly horrified by some of your high school-era fashion choices. So yes, people are malleable. We change. The only thing that doesn’t really change, which billions of years of evolution can attest to, is that we are lazy, goal-directed organisms.

Because our eyes enjoy someone whose face is “easy on the eyes,” I present the logical foundation: our minds prefer information that’s “easy on the brain.” It’s hard to unsee this idea once you see it:

Our minds prefer information that’s easy on the brain—we lean towards whatever doesn’t upend our pre-existing beliefs.

The Mere Exposure Effect

Merely being exposed to something makes us like it more. It’s why companies pay more money to have their products placed eye-level in grocery stores. There’s no magic here, just a process of repeatedly learning to pair “this thing” with “nothing bad happening.” When we learn that something is safe, familiar, it becomes likeable in its own way—even if we never have any intention of moving back to Buffalo or wherever we graduated high school from. Even if you aren’t besties with the guys at your gym, there’s something comforting about seeing them when you get your weekly pump on.

We like things that remind us of other things that we like. We love our own hunches and information that confirms our hunches. We like information that we get from other people, and that seems to gel with what we already know. All of these cues hold a torch to something: this is good! Learn this! Pay attention here! Information that’s easy to process feels good because we can relate it to other things we already know.

Fluency

When discussing your English/Spanish/Korean/Python know-how, fluency refers to how easily we can process a language. The more fluent you are, the less effort it takes to decipher a message. But fluency can also refer to the way we handle other pieces of information, or thinking itself.

Reading something in your native language; a name like “John,” smooth shapes: these are all fluent. Disfluent things: a name like “Craaüµqqq,” text that’s printed in a weird font, music in a genre you’ve never even heard of, for example—these are all more difficult for our brains to process, which makes them feel a bit off. Fluency is like love or porn—we get it, even if we can’t always describe it—but researchers have discussed the “warm glow” of what’s familiar or easy to understand since 1910.

The faster our brain can process or understand something, the more fluent a thought it is—and this is what can trigger a positive emotional response. Neurons that fire together wire together, so seeing a pattern for the umpteenth time—information that our brain knows precisely what to do with—means less processing volatility for our neurons, allowing for more energy efficient categorization of a new piece of information.

We prefer new pieces of incoming information that fit in nicely with whatever filing system it already has in place.

Change is Harder Than We Realize

When the scale is leaning, we’re more likely to pick up marbles that belong on that side. With your new and nifty balancing scales metaphor, just think about how far back this goes:

- Our brains are inherently lazy

- We like information that fits into the filing system our brain already has in place; when something sounds familiar, it’s easy to assume it’s true

- There’s no such thing as fact-checking, say, society

- The source of our hunches—repetition—has nothing to do with how true the information actually is

- We don’t fact-check our hunches

- Culture is just a group of brains working together

- It’s very easy for a group of people to all be wrong about the same thing

Confirmation Bias and Commitment

When it comes to fact-checking, the more mental reshuffling we’d have to do, the more likely we are to say that something is false.

If we come face-to-face with conflicting ideas, we tend to change whatever belief is easiest to change—or we simply dismiss the one that challenges our worldview.

Once we’ve made up our mind and our scale leans in one direction, we tend to dismiss new information that threatens our worldview:

Think about narcissists, psychopaths, or anyone you know who might be classified as delusional. If someone has information that threatens their worldview, they simply reject it and continue on with their day. As long as other people back you up, it’s impossible to get perspective on your beliefs.

- My teacher just gave me that grade because she’s jealous. This was a total fluke.

- People thought my essay was brilliant, so you don’t know what you’re talking about.

- My theories on lizard people ruling the earth aren’t extreme! I know thousands of people around the world who agree with me.

We might call these people crazy, but they’re doing what we all do—being selective about what information we believe—which is made easier by surrounding yourself with people who share and reinforce your ideas.

Once beliefs take hold, it’s hard to see the world any other way—it would mean throwing out all of those marbles we’ve been collecting over the years—which is why getting your ego attached to a specific finding or outcome is deadly for learning new information.