Table of Contents

What the Well-Read Amateurs Know

How You Can Know Little, Despite Seeing the Same Studies Over and Over

Based on years and years of writing about science and studying psychology, here is my Grand Unified Theory for Why It’s So Easy to Overestimate Our Knowledge of a Topic.

Let’s say you want to learn about psychology/architecture/physiology. First, that’s easy! We’re all lifelong students of behavior/buildings/bodies. So you’re starting here:

Then you start reading and filling in that area of your knowledge.

What the Well-Read Amateurs Know

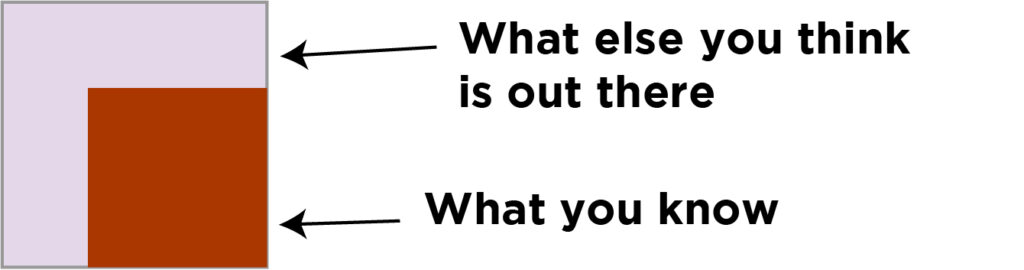

You’re learning. Maybe you’re reading lots of blogs. Some articles. Books. And after all of this, you’re starting to see the same research studies and term being used and repeated, over and over. You know about the Asch studies on conformity. The Stanford prison experiment. The marshmallow test. You’ve seen a lot of the same cognitive biases, over and over. Over and over.

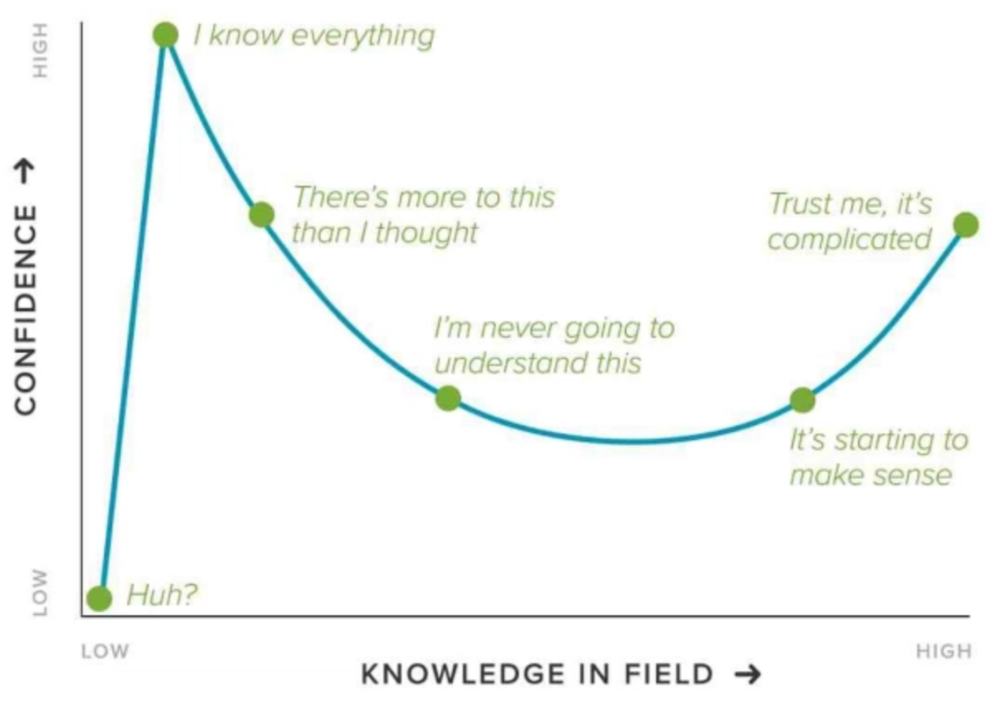

So that’s where a lot of well-read amateurs are. This is the Dunning-Kruger effect: “an illusory superiority that comes from the inability of people to recognize their lack of ability.”

You don’t know what you don’t know. It’s easy for a well-read amateur, a weekend warrior, to be unaware of their blindspots for many reasons: first, most people compare themselves to people who know less than they do. This is called a “downward social comparison,” and it’s a great way to make yourself feel better. Maybe you’d get a better grade than that person, or most others—but how much do they know? You don’t have an objective point of view here. Without using an objective measuring stick, it’s easy to fall into complacency. (Especially when learning feels difficult, and you’re getting by just fine with the information you do have.)

So, by this point, you feel very smart and well-read.

Here’s the thing: you’re not.

What you don’t know is that the chart actually looks like this:

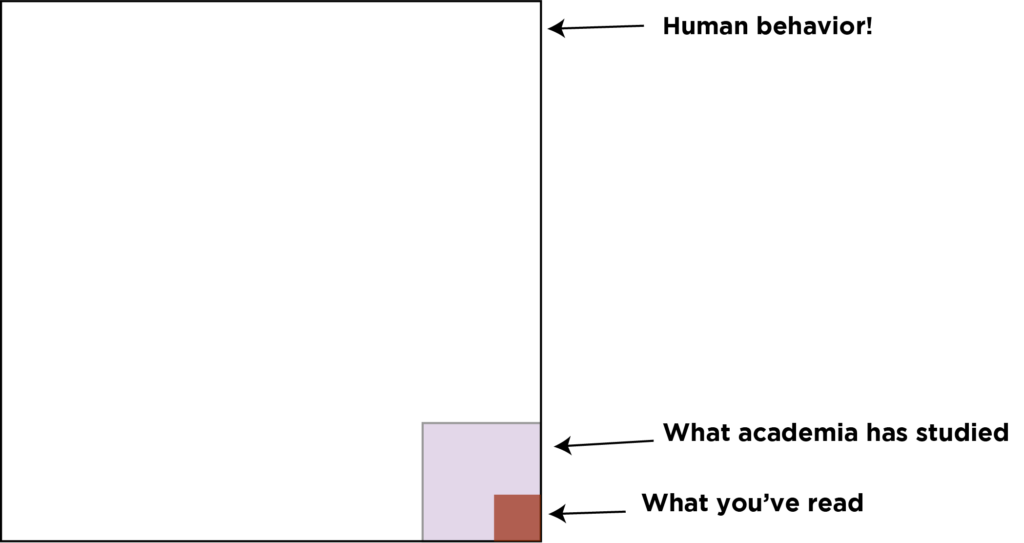

Our blindspots are HUGE. HUGE.They’re more like this:

How You Can Know Little, Despite Seeing the Same Studies Over and Over

There are a million reasons why a study or entire area of research could be in that unknown white area. A lot of our blindspots exist because of the way that scientific information tends to spread to the general public, which is very similar to the way that cultural items—movies, music, books—become hits. It starts with the creation of a study. We’ll use wine to symbolize a study, because whenever a study makes it through the process of being peer-reviewed, it’s also time to test one’s tolerance for booze:

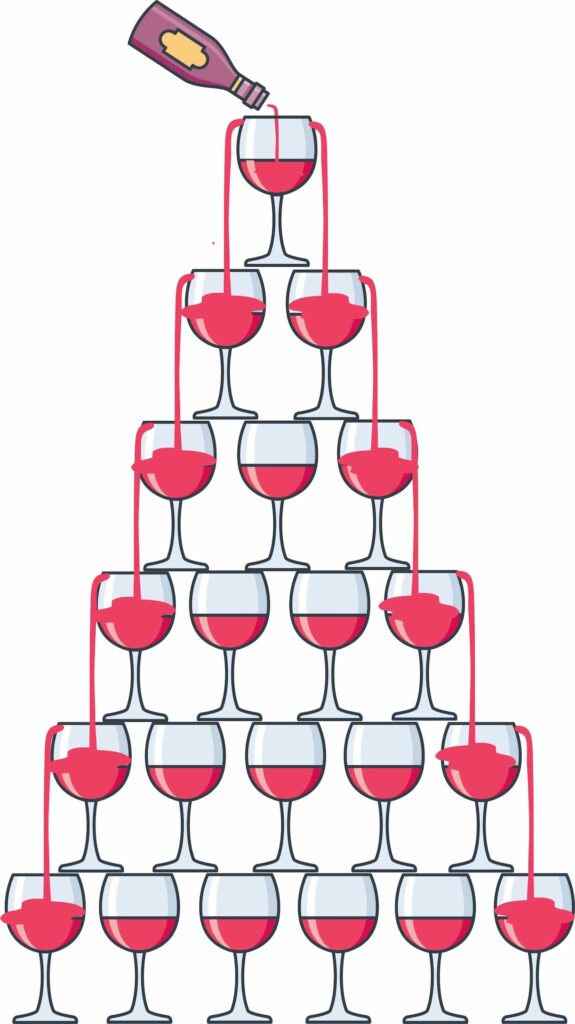

On its own, a single study will get published in a journal, like the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, the Journal of Health Psychology, or Psychological Science. If a study is vibrant, related to something in the news, or particularly interesting, psychology writers might help spread it out into the universe, like so:

It might be a slightly nerdy, technical website or publication that’s not very popular. But what’s in the glass is always easier to read than what’s in the bottle, so it spreads a little more. Depending on what journalists and editors see and find interesting, the media attention might stop there. Or it might keep going, getting spread out to more places.

Eventually, you start getting a “superstar” effect, where it’s everywhere. This is the marshmallow study, your Stanford prison experiment, your Asch conformity studies: they’re the Taylor Swift of psychology experiments. They’re like memes: you can’t get away.

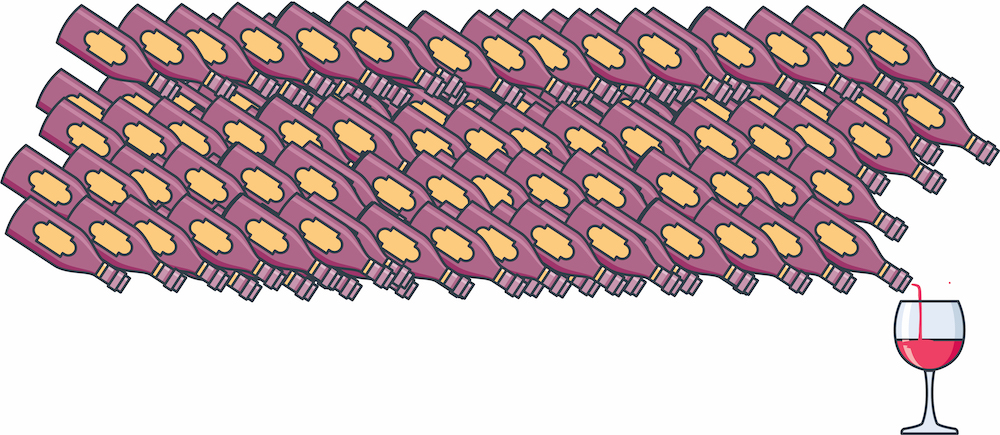

Because you know so many of these and keep seeing them everywhere, you feel fine filling in your square even more. Now, what don’t you see? All of the scientific knowledge, studies, and information that was never written about in the media at all.

Some of this wasn’t published as a study: researchers collect tons of unused data. Labs, funding, timelines, deadlines—all of these things are immensely complicated, and lots of information can get lost in the process.

Perhaps a researcher tried an experiment several times, but didn’t get a statistically significant result. There currently isn’t anywhere to publish information that would ultimately be helpful: “we did this, but nothing happened. Let this be a lesson to other labs, it’s a waste of time!”

Sometimes a study gets published in an obscure journal or doesn’t get picked up. Things happen. And if a study doesn’t get written about right away, the odds of it getting written about in popular media drop off very steeply, very quickly. Even if it’s a great study that links to a new, intriguing line of thought, you might never hear about it.

We know from the world of music that there’s no direct correlation between popularity and quality—but the idea that “it must not be that good if I haven’t heard about it” is all too prevalent. Why certain studies get picked up and become popular boil down to the same factors that influence our decisions on a daily basis: the whims of daily events and the opinions of tastemakers—popular writers, editors at prestigious publications.

HOW YOU CAN MINIMIZE BLINDSPOTS

If you’re doing research or want to learn about a new topic, I recommend learning about things in a systematic, deliberate way in order to minimize your blindspots. Learning requires building a good framework for the area you want to learn about, recognizing patterns, and maintaining a sense of intellectual humility: owning the fact that we all have blindspots.

- Read very basic texts in the area you’re researching: intro books are your friend. Get an overview. Remember: the area of a subject you’re interested in is just one tiny area of it. Divide a pie chart into several pieces: Social Psychology is always going to be just one area in psychology. It is not 95% of psychology. If it feels like one area represents the bulk of a discipline, that’s because your reading habits are lopsided.

- Find a syllabus for a class in the more specialized subdivision that you’re interested in. (You can restrict Google searches to education domains for better results.) Try a well-known university and a few less-known ones. (Professors are people with personal, idiosyncratic tastes, after all. They’re understandably biased towards their own line of research.) Read. You can often find free sources online.

- Know your living sources. Get intimately acquainted with Google Scholar, which lets you see how many times a paper has been cited and how influential it is.

- Get over your fear of going straight to the source. Identify key peer-reviewed journals in the area that keep popping up. Go there. Read. Read papers and abstracts that interest you. Sign up for email alerts when new articles are published. Brain and Cognition. APA Journals.

- Review articles and journals are a great way to read about trends from the past few years and theories that link current studies. Review of General Psychology. Annual Review of Psychology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. These are all things that I love.

- Identify key researchers in this area. Sign up for alerts on Google Scholar to find out when they publish new articles. Better yet: visit the website of a lab or researcher you’re interested in. Reading how they describe their work, and how their papers have evolved over the years, is a wonderful way to see how ideas evolve over time.

- Test yourself! Write blog posts and papers. Take quizzes. Reading alone doesn’t mean that you’ll retain all of the information.

- If you ever find yourself saying “now you’re just complicating things,” or “that’s ridiculous, you’re just splitting hairs,” back up. That’s a sign that you’re missing enough context to understand why something is important. (It’s also a sign of defensiveness because treasured opinions and worldviews are being questions.) Things really are complicated.

- Researchers are people who have their own cognitive biases. They’re not perfect. The process of collecting data, getting funding, and publishing a paper are all run by humans with their own motives and agendas, even if they’re not aware of what they are. Leave your ego at the door. Stay interested in learning for the sake of learning, rather than learning in order to back up a hunch or idea.

- Just because multiple people agree says nothing about how accurate those beliefs are. It’s possible for everyone to be wrong at the same time. (See: what we believed a few decades ago.) Science progresses one funeral at a time.