After I signed papers for my book deal, I started reading everything I could about how authors actually write books. Why? I had never written a nonfiction book, yet I was under contract with a German corporation to write a book.

What do the days of authors look like? Where do they even start? (I have a hunch that writers are especially prone to this “Am I doing it right?” fear because while we might get to see people writing articles in a newsroom, we get to see authors working on a book as frequently as we get to see my brother admitting that he’s wrong: it just doesn’t happen.)

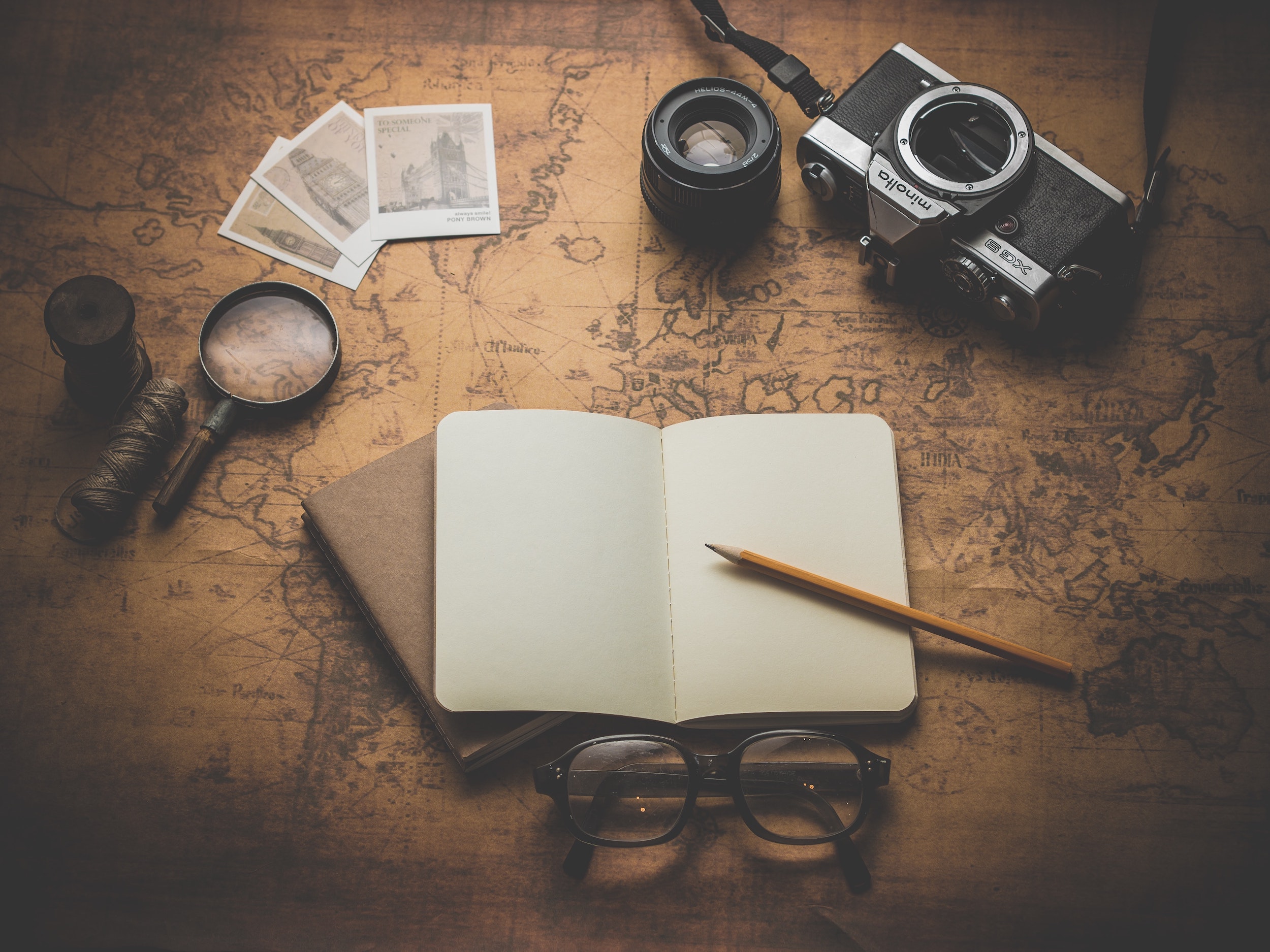

First, I had to do lots and lots of research. But what tools do authors use to organize their research? I wanted to do this impeccably, because I wanted every point I made in my book to be bulletproof, fully backed by great research.

I started using DevonThink because of this post by one of my favorite authors, Steven Johnson. DevonThink is also used by Ph.D. students to organize the research used in their dissertations; the manual is hefty and it involves a lot of tagging, uploading, and folder-creating.

Johnson used it for its AI: for years, he’d read books and religiously copy and paste passages of interest into DevonThink. Then, after opening up one of those passages (shown), he’d click on the nearby “See Also” button. The program would auto-magically summon other passages, making multidisciplinary connections that Johnson is known for.

I spent more hours than I’d care to admit learning how to use DevonThink, inputting passages, and troubleshooting the 3.5 gigabyte database I ended up creating. I developed a routine of reading ebooks, highlighting passages, writing notes, and then transferring the notes to DevonThink via Calibre, an open-source ebook management tool.

I bought Scrivener, which everyone seemed to use to write. Plus, the program can help organize research. Like DevonThink, getting the full benefits of its capabilities depends on how much time you spend on the input end of the process, adding metadata, links, notes, bookmarks, and folders to organize the data and PDFs connected to your document.

I bought the premium version of Evernote so that I could read research on my phone. More folders; more tags; much uploading.

I started compiling PDFs of research papers on my computer into different folders on my hard drive and color-coding those folders. I used tags. I used so many tags. (I did this in case I didn’t feel like using one of those other expensive programs that still felt unintuitive and cumbersome.)

I spent about four years reading about psychology, compiling research, and fine-tuning the book’s outline before I started seriously working on the draft.

I emailed tons of author-friends, as well as authors I’d interviewed over the years, for advice on all of this. The most common tip I received from friends echoed what ended up being the most useful piece of advice on this list—which was not directly about organizing:

Don’t wait too long to start writing

I did not want to believe that advice. I wanted the inside scoop of how writers actually write books. Surely, that advice was silly. But there it was again, in an email from someone with a few solid books under his belt:

I strongly recommend that you begin writing much sooner than you might think feasible—certainly before you’ve done all the reporting.

And yet again:

Just start getting words on the page. Believe me, there will never be a time when you say to yourself, “I’ve done all the reporting I need to”; you need to cut the cord and start drafting, or it’ll go on forever. There is literally no downside to starting the drafting process.

An acquaintance who ended up being 100% correct

I did not want to believe that advice; I wanted the secret. The thing that professionals do. The secret, it turns out, is that there is no secret: the best way to write a book is to just start writing a book. And big projects take a lot of work for everyone.

Writing helps you figure out how to organize your research because it forces you to figure out what you actually use while writing, and what method works best with your own writing process. There is no singular “best” way to organize your research because everyone’s brain, method of gathering information, and writing process is different.

My obsession with the perfect system to optimize my productivity and organization stemmed from my own anxiety about somehow doing it wrong.

The best way to get over the anxiety of writing is to simply do the thing that you’re anxious about and develop a habit of practicing self-compassion. If you’re learning and making progress, you’re not doing it wrong. Improving and developing a method that works for you takes time for everyone.

There is no “perfect” method; everyone’s brain works a little different. I have an easier time connecting dots and remembering research, but can struggle finding the right story.

I went through two hard drive meltdowns, an erased DevonThink database, and a frozen Kindle that deleted two years worth of notes. I ended up organizing the PDFs into folders on my computer, one for each chapter.

I used Scrivener to write the whole thing.

And how did I organize the structure? COLORED INDEX CARDS.