Table of Contents

The Problem with Productivity: Birth Place of the Egosystem

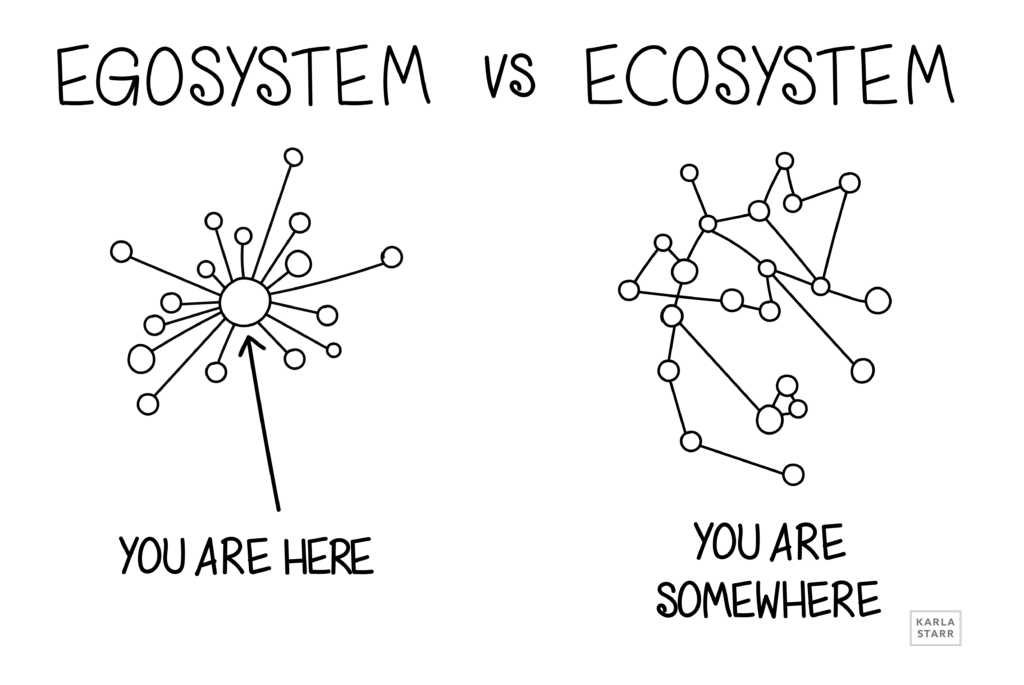

In 2008, social psychologist Jennifer Crocker laid out a framework for how people view their relationships, and how those views influence everything they do. In short, some people think that relationships intrinsically add value to their lives, while others fundamentally view relationships in terms of what value they can extract from them.1Jennifer Crocker. (2008). From Egosystem to Ecosystem: Implications for Relationships, Learning, and Well-being. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego (pp. 63–72). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11771-006

Egosystem

People with this view are self-centered, primarily concerned with their own needs and wants, and view their relationships as zero-sum.

Largely directed by self-presentation goals.

Lower generalized trust of others; “tit for tat.”

Believe they have to fulfill certain criteria to have relationships, and have those needs met by others (eg., make $$$ to be loved and respected); this overall goal supersedes the others.

Ecosystem

People with this view are other- or relationship-centered, viewing relationships as valuable and worthy of investments for their own sake.

Governed by compassionate goals.

Give others the benefit of the doubt.

Because they believe their needs will be met simply because others care about them.

Because they believe that their futures are linked to others, believe that acting selfishly also harms the self.

It’s a zero-sum mindset that leads people with an egosystem, “Me vs. the World” orientation down a rabbit hole of unhappiness: they see other people as standing in the way of their goals.2Jennifer Crocker and Amy Canevello. “Relationships and the Self: Egosystem and Ecosystem,” in APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology: Vol. 3. Interpersonal Relations, edited by M. Mikulincer and P. R. Shaver. American Psychological Association, 2015.

The problem with viewing other people as obstacles to what you really want in life—unless they are behaving in a way that actively and obviously fills some personal need—is that we’re destined to spend our lives in the company of others.

When you care more about your own goals than your relationships with other people, you view interactions as interfering with your goals. You may recognize “something standing in the way of what’s really important to me” by another name: stress. Other people’s needs, wants, desires, seem like unnecessary crap that has to be minimized and outsourced.

At the end of each day, there’s a good chance you say something like I did not do as much as I possibly could have. You might be obsessed with optimizing your life, doing more, and getting things done, and cranking things out. You like the idea of the 80/20 rule: do more, with this one neat trick!! There’s no shortage of productivity porn and tips about how to squeeze the absolute possible amount of value out of each day. Have you stopped to think about where this ideal comes from?

One explanation is that it’s a sign that you’ve internalized the Protestant work ethic and capitalism: If “generations are characterized by crises,” as [author Malcolm] Harris argues, then ours is the crisis of extreme capitalism.“

Consider the language we use: I wasted a day. I spent my time well. Just as corporations maximize every dollar, we’ve been trained to equate the value of our time with money, and try to squeeze out everything we can out of each minute.

It doesn’t occur to us that there’s an efficiency to every aspect of our life, to everything we do. And not only is there an efficiency, but we have control and influence over that efficiency. It’s something we can take responsibility for and improve. – Mark Manson

First, I want a pound of whatever Mark Manson is smoking, because this relentless drive to identify and eliminate inefficiencies is soaked into our cultural mindset—the hustle culture, the daily grind, the obsession with optimization. The constant thought I probably could have done more today, did I get 1% better? is a horrible dynamic to have in the background of our lives.

Back to the Pilgrims

When we’re obsessed with achieving our goals as efficiently as possible, we start noticing all of the things that feel like they’re getting in the way. And have you ever noticed that other people are simply not on your timetable?

What some people see as strings tying them down, or entanglements in need of pruning, are actually the makings of life’s greatest safety net, and its source of transcendent meaning and one of the biggest factors influencing our happiness in life: the quality of our bonds with others.

Stress is a threat to homeostasis—something forcing you to change in order to survive, a perceived different between what you have and what you want that’s of great importance. The inefficiencies of life (people) are also one of its greatest sources of meaning and joy.

In addition to being everywhere, you may have noticed that other people have free will. They cut ahead of us at the supermarket, forget to turn off their signal, and buy the last good loaf of bread3As I’m self-employed in the era of COVID, most of my recent interactions have involved going to the grocery store

Back in the Pilgrim era, participation in the economy demanded little more than keeping good relationships with your neighbors, and people were continuously in debt to others in the community for goods and services. “The presence of outstanding accounts assured the continuing circulation of goods, services, and social interactions through the community: Being under obligation to others and having favors owed was the mark of a successful person.” 4Stephanie Coontz. The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. (New York, NY: BasicBooks, 1992): 70–71.

Being happily entrenched in a social ecosystem was seen as a sign of success: being a neighbor among neighbors and a worker among workers. What the Pilgrims saw as success mimicked the ingredients of a happy life.

Today, we look up to the Elon Musks of the world because they invent things and lead companies—but they’re also workaholics. (Are they happy? Who knows.) We read business magazines, blogs, and self-help books written by industry leaders who claim to have cracked the code of productivity,

Read that website, that post, that book, buy that app, try that time tracking device, make that spreadsheet, follow that system: finally feeling like you have your shit together is right around the corner. Maybe you’ve found something that actually makes a difference, and now you’re telling everyone. You’re on message boards, taking pity on others who aren’t using your genius devices or methods.

We’re convinced that if we could just do a little bit more everyday, we’d eventually get rich, be respected, and feel comfortable with ourselves.

Destination Addiction

Let’s call this Destination Addiction—the idea that our lives will be better once we get somewhere else, conquer the biggest obstacle that’s currently on the horizon. Once we finally figure things out. Once we pay off our bills.

But we’ll never get “there”—once we do, our “there” will become “here,” and we’ll simply have another “there.”

Feeling guilty about our “lack” of productivity says more about the expectations that we set for ourselves and what we think we should be doing.

Like diet gurus selling supplements, workout gadgets, and diet books, the entire industry of productivity porn capitalizes on our insecurity—the vaguely uncomfortable feeling that behind closed doors, we’re not doing as much as other people. That behind closed doors, we’re not as good as other people, and are doing something wrong.

No one knows exactly what goes on in the kitchens of fitness models or the offices of tycoons—all we know is that our abs are hidden behind a layer of squishy skin, and our bank balance isn’t something we can brag about. We’re not getting as much done as other mothers, CEOs, pet parents, husbands, etc.

It’s a natural instinct to engage in the social comparison process and get a sense of where we lie in the pecking order of the group. Accurately gauging our status compared to others makes interactions smoother, and acts as a shortcut, telling us what kind of jobs and friends to look for, and what we can expect from others. We want to get as close to the VIP table as possible while avoiding rejection and humiliation, processes that would have been death sentences in earlier eras.

To repeat: this isn’t a flaw or a bug, it’s not the result of being narcissistic or self-centered. It’s a survival mechanism that evolved for the overall benefit of successful group living.

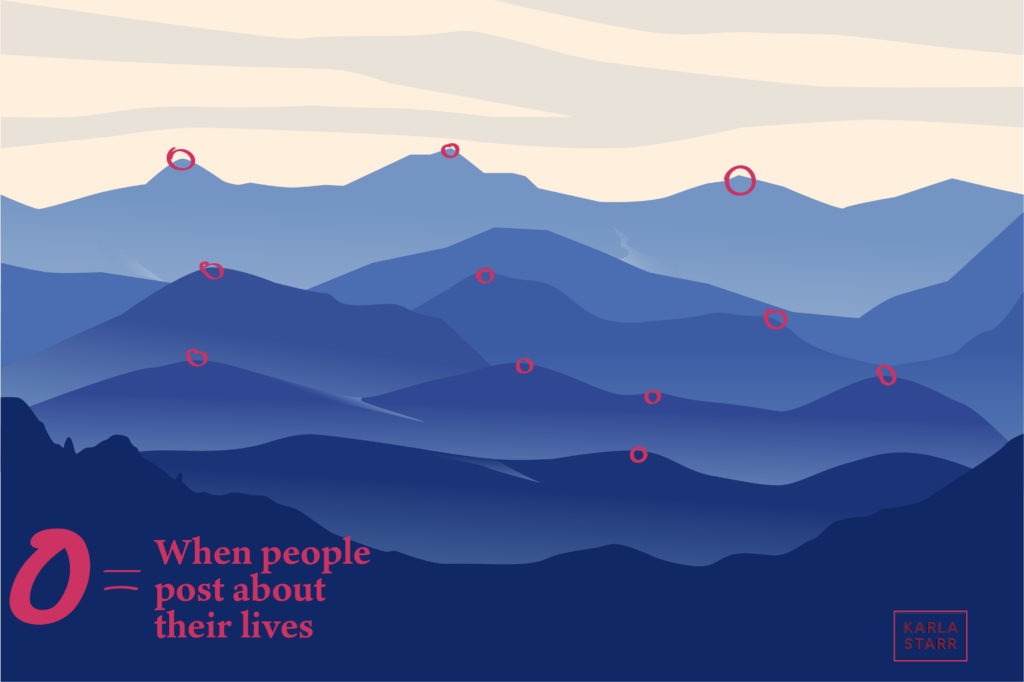

One big problem is that our innate, automatic social comparison processes are typically only exposed to everyone else’s highlight reel:

We’re not just exposed to our friends’ highlight reels, we’re exposed to the highlight reels of the most extreme people.

Comparison is the thief of joy. It doesn’t matter how your productivity stacks up to others (see: mastery vs. performance goals). And in the long run, it doesn’t matter how productive you were today.

Maximizing Your Long-Term Self: Stop Thinking About Efficiency

The main objective of your time doesn’t have to be constantly producing. The fact that you’re alive means that you did plenty: you’ve been moving, eating, surviving. Socializing, relaxing, recharging. Cleaning, organizing, dreaming, reading. Napping, reflecting, resting.

So-called unproductive things are vital because they’re what let you play the long game. They charge your battery. And isn’t that important to be productive? Or just survive? I ’d never thought about how much my self-esteem was tied to the idea of being an author until my book came out. The second it did, I felt good about myself. I held my head up a little higher. And here’s what happened when I was walking around the streets of NY: no one gave a shit. Nothing. Most of my daily interactions were better because I felt better, like I finally had the intellectual validation I’d been craving all along.

If you feel like you have to do something special to feel good about yourself, you have a fragile, unstable self-esteem because your self-worth depends on reaching certain goals. You don’t see everyone on earth as a flawed individual deserving of love, each with a unique set of strengths and weaknesses to bring to the table. You see life as a pecking order, a constant social struggle that increases how much stress you feel on a daily basis.

To play the long game, focus on these things:

- Your health

- Financial stability

- Quality relationships

- Connection with something larger than yourself

- Joy and meaning in daily activities

Your time and energy are the only worthwhile things. Taking breaks to explore and resting to keep your batteries as charged as possible are more important than working on Your Thing for another hour.

It doesn’t matter if you finally achieve your life goal if that’s the only part of your life that you’re happy with: trust me.

When I achieved my life goal of becoming an author, I was miserable. The button on my book’s Amazon page changed from “pre-order” to “Buy It Now,” but I was otherwise lagging. Isolated. Unhealthy. I was still seeking validation.

Stay on good, stable terms with the rest of your life: it may take much longer to achieve that goal than you think. The happiness you’ll get from reaching that summit will be short-lived.5Timothy D. Wilson and Daniel T. Gilbert. “Affective Forecasting: Knowing What to Want.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 14, no. 3 (2005): 131-134.

Obsessing over efficiency and productivity today creates fragility in the long-run, prone to burnout and major disruptions from unpredictable events. Obsessing over productivity, in other words, won’t make you more productive or happy—it will only put you in a constant cycle of comparison and stress you out in the meantime.

Slow down. Live a rich life.6Shigehiro Oishi and Erin C. Westgate. “A Psychologically Rich Life: Beyond Happiness and Meaning.” Psychological Review (2021). https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000317 PDF here.

Resources

- 1Jennifer Crocker. (2008). From Egosystem to Ecosystem: Implications for Relationships, Learning, and Well-being. In H. A. Wayment & J. J. Bauer (Eds.), Transcending Self-Interest: Psychological Explorations of the Quiet Ego (pp. 63–72). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11771-006

- 2Jennifer Crocker and Amy Canevello. “Relationships and the Self: Egosystem and Ecosystem,” in APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology: Vol. 3. Interpersonal Relations, edited by M. Mikulincer and P. R. Shaver. American Psychological Association, 2015.

- 3As I’m self-employed in the era of COVID, most of my recent interactions have involved going to the grocery store

- 4Stephanie Coontz. The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. (New York, NY: BasicBooks, 1992): 70–71.

- 5Timothy D. Wilson and Daniel T. Gilbert. “Affective Forecasting: Knowing What to Want.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 14, no. 3 (2005): 131-134.

- 6Shigehiro Oishi and Erin C. Westgate. “A Psychologically Rich Life: Beyond Happiness and Meaning.” Psychological Review (2021). https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000317 PDF here.