As anyone who has ever favored one team over another knows, opponents have a habit of playing dirty and referees make plenty of unfair calls. But this happens on both sides.

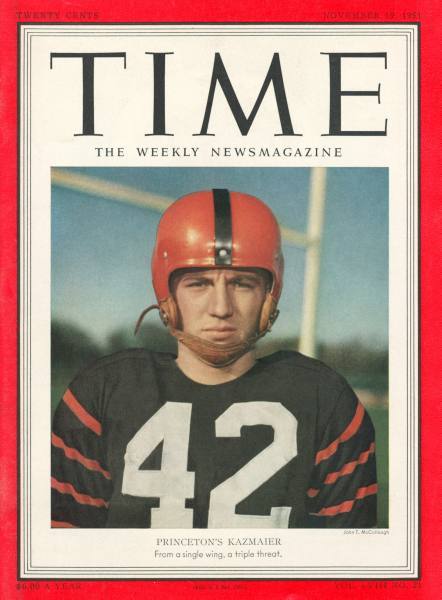

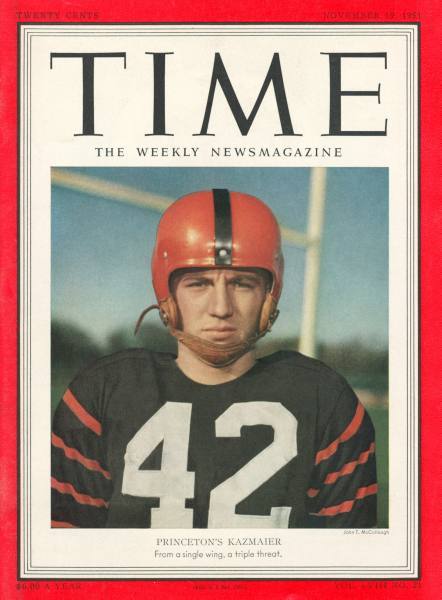

On November 23, 1951, Dartmouth traveled to Palmer Stadium in New Jersey to play Princeton. Here are some facts: it was the last game of the season for both teams; Princeton won; this was some nasty-ass playing. The game’s star—Princeton’s Dick Kazmaier, who had been featured on the November 19, 1951 cover of Time magazine—left the game after sustaining a concussion and breaking his nose. His teammates also played rough; one Dartmouth player broke his leg.

Was this Ivy League version of a shivs-out prison brawl the norm for college football back in the day? According to the Daily Princetonian:

This observer has never seen quite such a disgusting exhibition of so-called “sport.” Both teams were guilty but the blame must be laid primarily on Dartmouth’s doorstep. Princeton, obviously the better team, had no reason to rough up Dartmouth. Looking at the situation rationally, we don’t see why the Indians should make a deliberate attempt to cripple Dick Kazmaier or any other Princeton player. The Dartmouth psychology, however, is not rational itself.

The brilliantly-named Dartmouth printed its own version of events:

Dick Kazmaier was injured early in the game. Kazmaier was the star, an All-American. Other stars have been injured before, but Kazmaier had been built to represent a Princeton idol. When an idol is hurt there is only one recourse—the tag of dirty football. So what did the Tiger Coach Charley Caldwell do? He announced to the world that the Big Green had been out to extinguish the Princeton star. His purpose was achieved.

After this incident, Caldwell instilled the old see-what-they-did-go-get-them attitude into his players. His talk got results.

Princeton fans claimed to have moral players who had the misfortune of sharing the field with Dartmouth hooligans. Dartmouth reported said that their civilized athletes were targeted by some nasty Princeton boys.

We win because we’re good; we lose because of bad luck. Our opponents win because they got lucky and lose because they’re objectively the worst. We are just and we play fair.

We are just; the other team is full of horrible people.

In the classic study, “They Saw a Game: A Case Study,” students from both schools watched a movie of the game and filled out a survey. When asked which side started the rough play, 86% of Princeton students blamed Dartmouth; 53% of those at Dartmouth said that “both sides” started it; 36% admitted fault.

Researchers seemed shocked that everyone was 100% convinced that their version of events had been the objective truth. The other side looks delusional; but from their point of view, we’re just as crazy. Everyone is a bit biased.

Our brain is an infinitely complex bundle of networks. On its way to the visual cortex, the things we see pass through the orbitofrontal cortex, one of the brain’s hedonic hotspots that’s linked to “affective significance,” adding an emotional tone to information. Neuroscientist Luiz Pessoa argued “Vision is never pure, but only affective, vision.” Our emotions, motivations, preconceptions, and feelings are involved in how we process information even before we ever see something.

As those psychologists wrote in 1954:

It seems clear that the “game” actually was many different games and that each version of the events that transpired was just as “real” to a particular person as other versions were to other people.

Other people are delusional: this is fact. But us? This cognitive bias has a name: the bias blind spot. We’re often unaware of the fact that we’re distorting reality. Even though everyone is 100% certain that their interpretation of events is the objective truth—it’s what we saw with our own two eyes!—it’s just what we saw through our own skewed eyes.