On February 16th, I got an email from Randy, the man whose name is on my birth certificate. “It’s important that I [talk] with you, hopefully reasonably soon.” We spoke on February 22nd for the first time in 18 years. I thought, perhaps, that he’d have changed somewhat during that time—that he’d have a job, a career, finished a project, gotten a hobby. Something.

Why didn’t he have a job? His employer wasn’t treating him well, and his wife made enough money for the both of them to live. (Previously, he’d lived with women who supported him after similar spats with employers.) But his wife didn’t make enough money for him to do anything he really wanted to do—travel, take photos, and finally live. He was angry at the world, his father for how he died, his sister for how she handled the aftermath, his wife (who he was thinking of leaving).

After a while, I recognized what I was dealing with: a man who hadn’t changed in 18 years.

Why? Nothing was ever his fault.

The One Cognitive Bias to Rule Them All

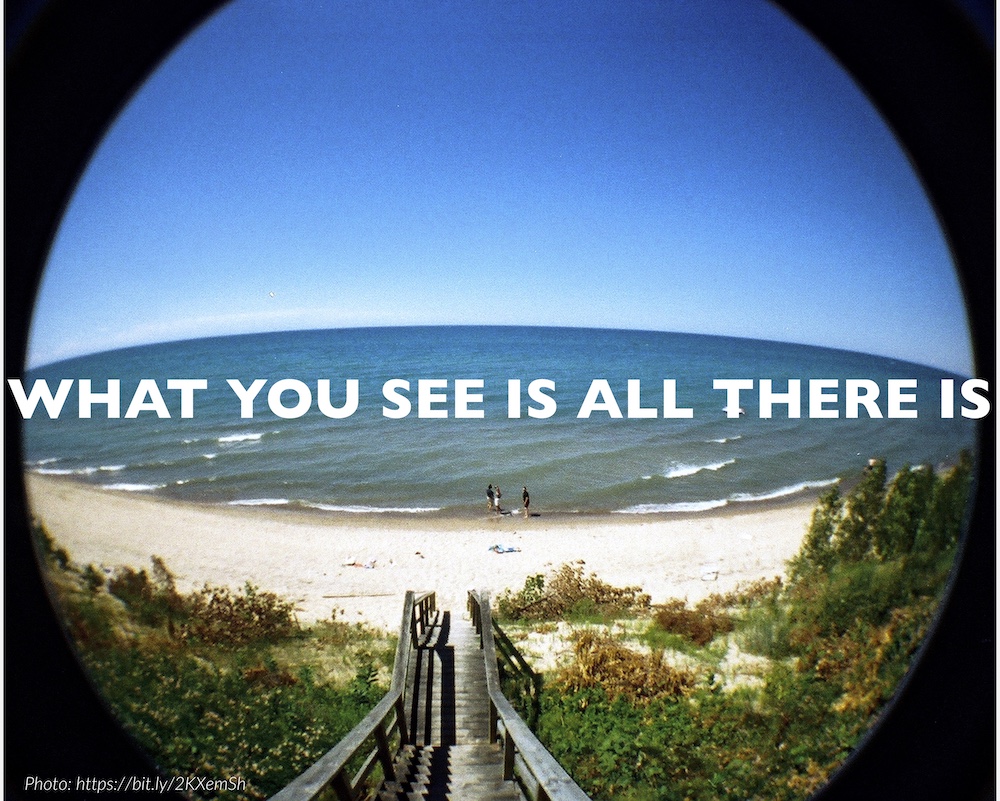

Here’s what Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman called the granddaddy of all cognitive biases: “What You See is All There Is.”

We see life as though we’re looking at it through a fisheye lens. For the sake of survival, it makes sense—that perspective helps us focus on our immediate environment. It saves us energy: we don’t have to think, we just have to observe. Whatever is right in front of our face demands our attention, so we don’t become someone else’s lunch. But while whatever is right in front of our face represents 100% of our world, it represents 0.000000000001% of the world. This is also our perspective when we’re young or immature: we’re selfish and self-centered. We focus on getting our own needs met and see our group as the center of the universe.

How to Become Wise: The Stages of Ego Development

First, think about someone you respect. Who is wise?

Yoda is wise, balanced, and knows that it’s not the center of the universe. Wise people always seem to have patience and know the value of time. They see the big picture. But Yoda wasn’t always Yoda…

The way we develop takes us from “What You See is All There is” to Yoda, and it follows a standard trajectory. It’s pretty fascinating. Here we go!

Stage 1: Impulsive. We’re the center of the world.

You know the drill here—just think about the prototype: babies.

- Babies lack a sense of object permanence: if they don’t see something, they think it has ceased to exist. Babies are the most self-centered being in the world.

- Their main concern is their body. “I’m uncomfortable, and if this continues then the world is going to end.” (Related note: I do not have children.)

Stage 2: Self-protective

People here believe:

- I’m the most important, but other people exist

- They don’t see the world in the same way that I do

- Rules exist

- If I don’t follow them, I can get in trouble

Stage 3: Conformist.

We know:

- There are others, and—goddammit—we’re going to have to get along with them in order to survive.

- We’re part of a group, and need to cooperate in order to survive and be part of the tribe.

- We don’t have a deep sense of who we are; having others think of us as “fitting in” is as deep as we go.

Stage 4: Self-aware. Achievement-oriented.

Ooh, look—we’re learning! Because we’re gaining a sense of autonomy, we feel like we can be ourselves and be a part of the group. We can be critical of ourselves. We no longer feel the need to be completely shielded by the group. We’re really, really concerned with standing out from the group.

Stage 6: Conscientious

We’re know:

- We’re part of the group, because we’re human, and all humans are a part of the group. We’re so comfortable with belonging, with ourselves (just as we are), that we don’t feel the need to be special or stand out. We know that the group will be just fine.

End Stage: Autonomous and Integrated

The way we view our relationship to others and the world is complicated: the world is full of color, not black and white. Sometimes we’re right, sometimes we’re wrong—even both at the same time.

Instead of ethnocentrism or “now”-ism, we recognize that our group is just one of many, our time is just one of many. We’re willing to sacrifice some comfort for the good of everyone.

In a nutshell: we’re just a part

The path from self-centered to wise—baby Yoda to Yoda—is pretty clear. At the lower levels, it’s just us, seeing things in black and white; you’re for me or against me; then, it’s us and fitting in, us and standing out, us and close relationships, us and relationships with all of humanity.

At more advanced stages of maturity and wisdom, you realize that you are just playing one part in this crazy carnival of life—and that your position is no better than others, just different. Here, you can see yourself and the world more clearly and accurately: you’re not the center. Things aren’t black and white. If you’re not a leader or right at the center of things, everything is going to be okay.

Growing up is really the story of how much more interesting and complex the world gets when our ego gets quieter.

Our attention is limited, so the less that we need to put ourselves in the center of the world, the more space we make for the rest of the universe to come in and show us what we’re missing. Maturity is the development of perspective—of being aware that our perspective isn’t the only one, isn’t the only one that matters.

Wisdom, in a nutshell, is perspective, which is why it helps us compensate for the whole “What You See is All There Is” thing. Wisdom is what helps us understand that we are inseparable from others, and that the whole picture is more interesting than just our one little part. We’re interested in an integrated framework.

What’s standing in the way of growth: defense mechanisms

Maturity is about having a more accurate view of ourselves in relation to the rest of the world. When we’re young, we think we’re the center of the world. Our defense mechanisms are also known as forms of “emotionally biased information processing.” They’re what prevent us from hearing things that shake the narrative we have of ourselves.

You know how sometimes it takes a million years for you to find a photo you like of yourself? That doesn’t look like me! you say, not wanting to admit the very real truth that all photos of you look like you. When we avoid learning from other people’s perspectives or new information that’s hard to stomach, we’re failing to see something in all its complexity and failing to grow. Other people’s opinions of us are entirely true from their perspective.

“Anna Freud… argued that defense mechanisms are ways in which we distort reality in order to protect the ego from feelings of anxiety… In each of these cases we process information in accordance with a self-serving bias that enables us to believe what we wish to be true. (Resistance to Belief Change, 111

When we have a wall of defenses up—a tall one—we dismiss what others say about us. You might be a pediatrician for disadvantaged kids/volunteer firefighter and generally good person, but if someone else’s only interaction with you was dealing with an impatient version of you at a pharmacy, they’re going to see you as a jerk. (Even if you were impatient because, say, someone was dying.)

It’s a hard truth to hear that others don’t think we’re the best, that we’re not really that important to everyone else, and that we’re only playing a bit part in the lives of others. It’s easy to process information in a self-serving way and look outside for the blame, at something that isn’t our behavior:

- because my father was a drunk/didn’t love me

- because they made fun of me when I was little

- I’m not being an asshole, I just wasn’t born with social skills

- I’m argumentative and difficult, it’s in my nature

- they didn’t like my essay because I’m a woman

Defense mechanisms interfere with our ability to process new information. We might obsess, avoid, or ghost someone, stewing in a pot of rumination and resentment. Notice: we’re never really defensive about something unless it’s hitting a nerve. I don’t care if someone says “you suck as a cellist” or “you only got a book deal because of your height.” I’ve played the cello once, and thanks to the internet, no one I work with even knows how tall I am.

The problem is when our desire to hold onto these beliefs about ourselves start interfering with our ability to adaptively function in the real world. A lot of people manage to hold onto maladaptive beliefs by shrinking their world. Example: if you’re an alcoholic who doesn’t want to face the consequences of your drinking at work, you might decide that consulting/freelancing is a better fit for you. If you’re unwilling to examine your dysfunctional beliefs about relationships, you might decide that “there are no good men/women.” If we don’t want to face our dysfunctional eating habits or failure to exercise, we’ll blame getting diabetes entirely on our genes.

We have defense mechanisms for a reason: they’re protecting a part of our ego, a part of our identity that we so desperately want to be true that we’re willing to distort reality. They defend us and protect us. We might not even know that they exist until they outlive their usefulness. Defense mechanisms actually serve as the infrastructure around us, sifting the information that we’re willing to learn. They help guide us and our beliefs. We get defensive when we feel like we’re being attacked—and the more defensive we are, the more likely that we’re coming up against a painful truth.

They start interfering with our lives when we engage in these so-called “maintenance process” that feel like self-righteous anger, growing a chip on our shoulder, carving that groove more deeply into our subconscious.

To put it another way, defense mechanisms are mechanisms that permit us to think and act. Although their most manifest function is that of protecting us from anxiety, defense mechanisms are the primary instruments for creating order in the mind. [1]

In truth: who cares if that other person believes that thing? We are still us.

How to predict someone’s future

It’s only when we have no defense mechanisms that we can more clearly you can see the world, yourself in it. The best way to predict someone’s future is to look at their beliefs about the world, how they make sense of new information, and how well they incorporate this into their lives. I have a feeling that I know exactly where my father, and various former coworkers, are going to be in the future: exactly where they are, right now—old and alone—because they are never wrong.

They fail to see that other people’s perspectives are valid. They fail to see the world clearly and accurately because they can’t hear hard truths about themselves. At one point, their defense mechanisms served them from the harsh criticisms of their own fathers. Rejected from their peers, they took solace in areas of life where they felt superior; they remain locked in those cages, and fend off anyone with an opinion that doesn’t cast them in a flattering light.

The way through is self-compassion.

“Learning how to be kind to ourselves, learning how to respect ourselves, is important. The reason it’s important is that, fundamentally, when we look into our own hearts and begin to discover what is confused and what is brilliant, what is bitter and what is sweet, it isn’t just ourselves that we’re discovering. We’re discovering the universe.” — Pema Chödrön

We’re blind to our own blindspots. How can we tell if we’re holding onto accurate beliefs?

- Defense mechanisms shrink our world, only allowing us to listen to things that confirm our beliefs in ourselves and the world. Pay attention to when you feel like lashing out. What are you avoiding?

- What would you lose, or how would you feel about yourself, if this was false? It’s mind-boggling how much of people’s beliefs and lives are subconsciously structured to let them feel good. It’s not all bad, mind you: it’s a part of our psychological immune system to believe that we’re okay.

- How would you feel if something was your fault?

- You can predict someone’s future by looking at how they process new information.

References

Quote on defense mechanisms, from: The Self and its Defenses: From Psychodynamics to Cognitive Science. Michele Di Francesco, Massimo Marraffa, and Alfredo Paternoster. Palgrave, 2016: page 150.